Review of the Day: Tales for Little Rebels by Julie L. Mickenberg and Philip Nel

True story. My husband’s best friend was dating a red diaper baby and one weekend we decided to stay in her parents’ cabin. Not entirely grasping her upbringing to its fullest extent we were amazed and delighted when we stepped into the home to find it cover from tip to toe in amazing radical Socialist publications and decorations. As a children’s librarian, however, my interest lay entirely in her old bedroom, still home to a fine selection of left-wing children’s literature. It wasn’t a large selection, however, and I was a bit disappointed not to find much beyond a cursory introduction to Russia. Into this void slips Mickenberg and Nel’s dual scholarship. A ribald, witty, sometimes fun, sometimes thoughtful examination of a wide swath of too little known literature, Tales for Little Rebels gives a thorough child-centric going over to everything from gender politics and African-American poetry to Leninism, Stalinism, Marxism, and all the other "isms" you could name. You will find nothing else like this on the marketplace today. Nothing quite as engaging, certainly.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

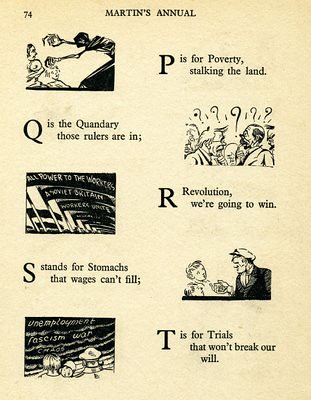

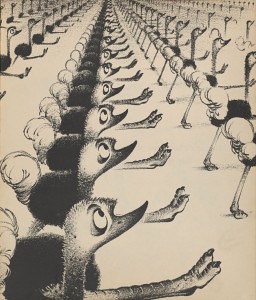

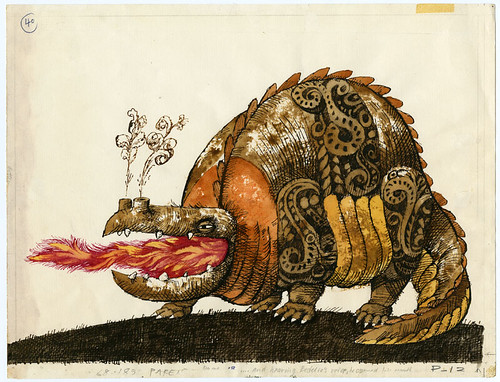

In his Introduction professor Jack Zipes states, "A radical literature, especially a radical children’s literature, wants to explore the essence of phenomena, experiences, actions, and social relations and seeks to enable young people to grasp the basic conditions in which they live." So it is that professors Julia Mickenberg (Associate Professor of American Studies at the University of Texas) and Philip Nel (Professor of English and Director of the Program in Children’s Literature at Kansas State University) have sought out and brought together a collection of too little known texts on a variety of different topics. The profs separate the book into eight different parts: R is for Rebel, Subversive Science and the Dramas of Ecology, Work Workers and Money, Organize, Imagine, History and Heroes, A Person’s a Person, and finally Peace. Each section contains text from a variety of different titles as they relate to the subject. For example, within the "A Person’s a Person" section you might read a story by Langston Hughes about a boy in a big city, an original text of Dr. Seuss’s infamous The Sneetches, a powerful critique of McCarthyism via Pogo, a look at that most peculiar and amusing of picture books X a Fabulous Child’s Story, a wonderful retelling of The Princess Who Stood on Her Own Two Feet, and an excerpt from the tale Elizabeth: A Puerto Rican-American Child Tells Her Story. And that’s just within a single section! When reprinting picture books, the editors make an effort to include many of the illustrations. When reprinting selections from longer texts, an equal effort is made to reprint whatever visual images accompany it. The end of the book consists of "A Working List of Recommended Radical Books for Young Readers," just in case you need some extra reading when all is said and done.

Interestingly, the book diverges from your average scholarly texts with its assumption that parents are naturally going to want to share these stories with their kids. For example, at one point the book states that "cries of `Down with capitalism! Long live the Soviet!’ demand a fair amount of explanation – so much so that parents may want to avoid sharing Donn’s rhymes with very young children." The editors are both encouraging these stories to be used for the purpose for which they were intended, and warning parents off of the more dated aspects. This is a rather singular thing to do, but it isn’t too surprising when you stop to think about it. Nel has always had a penchant for combining scholarship with use. His republication of Crockett Johnson’s Magic Beach was both a historical document and a legitimate picture book in its own right. Likewise the very notion of an The Annotated Cat in the Hat sounds ridiculous on paper, but Nel found a way to make even an easy reader both a great story and a singular piece of research. Tales for Little Rebels just follows suit.

Interestingly, the book diverges from your average scholarly texts with its assumption that parents are naturally going to want to share these stories with their kids. For example, at one point the book states that "cries of `Down with capitalism! Long live the Soviet!’ demand a fair amount of explanation – so much so that parents may want to avoid sharing Donn’s rhymes with very young children." The editors are both encouraging these stories to be used for the purpose for which they were intended, and warning parents off of the more dated aspects. This is a rather singular thing to do, but it isn’t too surprising when you stop to think about it. Nel has always had a penchant for combining scholarship with use. His republication of Crockett Johnson’s Magic Beach was both a historical document and a legitimate picture book in its own right. Likewise the very notion of an The Annotated Cat in the Hat sounds ridiculous on paper, but Nel found a way to make even an easy reader both a great story and a singular piece of research. Tales for Little Rebels just follows suit.

In terms of books that sought to highlight or honor a variety of ethnic groups, Mickenberg and Nel point out that a vast chunk of those writers were white as the newly driven snow. To make up for this, they’ve been careful to include backmatter for further reading of those race’s authors. Those that are featured, however, don’t mess around. I’ve always had an ingrained respect for Julius Lester’s work, but that may have had as much to do with the fact that the man’s a legend than anything else. Having read his story High John the Conqueror from the 1969 book Black Folktales I find my uninformed respect replaced by jaw-dropped bug-eyed shocked respect. Oh man. If you read no other story in this book, read this one. You have never NEVER read a folktale like this. It’s raw. It’s like the Richard Pryor of folktales. I almost have a hard time believing that it even got published. But these were different times, and now that I’ve found it I can’t wait to read the rest (and this in spite of Zena Sutherland’s scathing critique labeling it "a vehicle for hostility").

Of course, there was at least one type of children’s literature that did not make the cut. The interesting omission of post-apocalyptic texts may be due more to the fact that the book is concentrating primarily on picture books than anything else, but it’s still a definite gap. A cursory glance at children’s fiction shows that dystopian novels are a very strong and distinctive genre in and of themselves and one that is sadly lacking from this book. After all, even The Lorax could be considered an end-of-the-world tale, if examined in the right light. Yet Mickenberg and Nel eschew the "toldja so" school of thought, leaving me to wonder why that is.

Of course, there was at least one type of children’s literature that did not make the cut. The interesting omission of post-apocalyptic texts may be due more to the fact that the book is concentrating primarily on picture books than anything else, but it’s still a definite gap. A cursory glance at children’s fiction shows that dystopian novels are a very strong and distinctive genre in and of themselves and one that is sadly lacking from this book. After all, even The Lorax could be considered an end-of-the-world tale, if examined in the right light. Yet Mickenberg and Nel eschew the "toldja so" school of thought, leaving me to wonder why that is.

The term "dreary dogma" is invoked by Little Rebels to typify the kinds of didactic literature kids too often are forced to read quote unquote for their own good. Little Rebels is a conscious effort on the part of its editors to escape such ingrown dreariness. The stories told here for the most part crackle with energy and hope. Some are distinctly more imaginative and clever than others too. For example, while I found myself growing very fond of The Practical Princess by Jay Williams and even the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America’s Mary Stays After School or – What This Union’s All About, other texts just don’t stand close scrutiny. A play called The Beavers by Oscar Saul and Lou Lantz, for one, is written in an odd herky-jerky style that resists all attempts to read it smoothly from the page.

When you finish the book, what remains notable about it is the fact that Mickenberg and Nel aren’t poking fun at their subject matter. Finding abecedarian texts that contains lines like "K stands for Kremlin where our Stalin lives; L is for Lead he so ably gives," leaves the writer wide open for criticism. Instead, the editors choose to place each text within the context of its time. They acknowledge that some ideas in this book have veered too far in one direction without question, and that this is never a good idea, particularly when it comes to children’s literature. But as the book so ably states, right from the start the 1667 book A Guide for the Childe and Youth was ideological. The urge to instill our values in our children is ever with us. And what Tales for Little Rebels does so succinctly is to gather a representative sample of different kinds of ideals and show how many of them successfully brought about the world we live in today.

When you finish the book, what remains notable about it is the fact that Mickenberg and Nel aren’t poking fun at their subject matter. Finding abecedarian texts that contains lines like "K stands for Kremlin where our Stalin lives; L is for Lead he so ably gives," leaves the writer wide open for criticism. Instead, the editors choose to place each text within the context of its time. They acknowledge that some ideas in this book have veered too far in one direction without question, and that this is never a good idea, particularly when it comes to children’s literature. But as the book so ably states, right from the start the 1667 book A Guide for the Childe and Youth was ideological. The urge to instill our values in our children is ever with us. And what Tales for Little Rebels does so succinctly is to gather a representative sample of different kinds of ideals and show how many of them successfully brought about the world we live in today.

There is a great deal of thought to be had when you finish this book as to what "subversive" texts are being published for kids today. The initial instinct is to say that there’s nothing quite as gutsy or forthright today as something like Syd Hoff’s Mr. His. Once that instinct dies down a little, though, you might remember books like Jane Yolen’s Encounter, John Marsden’s The Rabbits, Marcus Ewert’s 10,000 Dresses, or Thomas King’s A Coyote Columbus Story. Subversive children’s literature is far from dead. It has merely taken on new battles with new tactics and tricks. Here then is a hope that in ten or twenty or thirty years someone revisits this topic and updates this text. It will always be with us. It will never grow old.

There is a great deal of thought to be had when you finish this book as to what "subversive" texts are being published for kids today. The initial instinct is to say that there’s nothing quite as gutsy or forthright today as something like Syd Hoff’s Mr. His. Once that instinct dies down a little, though, you might remember books like Jane Yolen’s Encounter, John Marsden’s The Rabbits, Marcus Ewert’s 10,000 Dresses, or Thomas King’s A Coyote Columbus Story. Subversive children’s literature is far from dead. It has merely taken on new battles with new tactics and tricks. Here then is a hope that in ten or twenty or thirty years someone revisits this topic and updates this text. It will always be with us. It will never grow old.

Oddest Note to Myself Written While Reading This Book: “pg. 233 – genital mutilation anxiety?”

Other Online Reviews:

Misc:

-

It’s Non-Fiction Monday, people. Jean Little Library has the round-up.

-

Listen to editor Julie Mickenberg interviewed about this book on the podcast Rabble (and is that Gaiman doing the intro or do I just have a bad case of Newbery on the brian?).

-

She is also on The Leonard Lopate Show (below "The Afghanistan Problem") where she discusses the book alongside contributors Charlotte Pomerantz and Joe Molner.

-

Read the next book online if that’s your fancy. Google Books provides.

-

This marks the first time a book reviewed on this site was also featured on BookTV. Check it out.

Filed under: Reviews

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Happy Poem in Your Pocket Day!

More Geronimo Stilton Graphic Novels Coming from Papercutz | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Environmental Mystery for Middle Grade Readers, a guest post by Rae Chalmers

ADVERTISEMENT