The Tycoon: Talking with Leonard Marcus About Abraham Lincoln, Our “Masterly Media Manipulator”

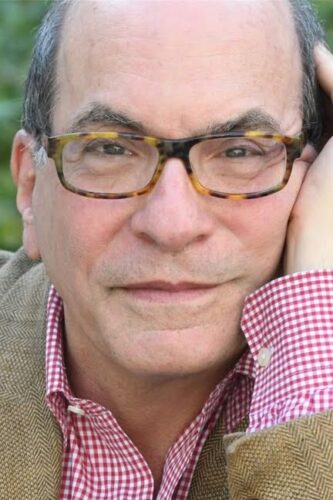

In the pantheon of children’s literature scholars of the early 21st century, no star burns brighter than Leonard Marcus. Indeed, no one really could challenge him for the throne. Whether he’s encapsulating the history of children’s book publishing in Minders of Make-Believe, giving context to the creation of Little Golden Books, or writing biographies of luminaries like Margaret Wise Brown, he’s the man you turn to when you want information about children’s book greats of the past.

That said, he’s not a man you can box into a single category. Indeed, I’ve read picture books he’s created and other fine and fun stuff for younger readers. Now, publishing as of today, we’ll see the release of his children’s nonfiction for older readers, Mr. Lincoln Sits for His Portrait: The Story of a Photograph That Became an American Icon. The book has already earned itself a Kirkus star who said it was, “A provocative study of Abraham Lincoln as a masterly media manipulator.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I can think of no better line to begin with. Today, I speak with Leonard about the book and all that it entails.

Betsy Bird: Leonard, thank you so much for joining me here today. You’ve done any number of biographies in the past, and your focus has primarily been creators of books for children. You may correct me on this point, but this is the first middle grade informational text I remember you creating, and its subject matter is a political and historical figure. The connection to books is undeniable, but where did this particular idea for a book come from?

Leonard Marcus: Well, actually a number of my previous books–A Caldecott Celebration (1998/2008), Funny Business (2009), You Can’t Say That! (2021), and others–were published for young readers. But I have always thought that good writing is good writing and have tried in every instance to make a book that an interested adult would want to read, too.

As for Lincoln as a subject, I have been fascinated by him since childhood. Growing up, I read everything I could find about Lincoln at our local library in Mount Vernon, New York, and I wrote my fifth grade “long project” about his time as president. My account of the assassination was riveting! As a history major at Yale, my favorite course was the one about nineteenth-century America taught by David Brion Davis, to whose memory I dedicated Mr. Lincoln. As it happens, Professor Davis looked a little bit like the great bearded man, and was also a stirring orator, although he did not as I recall speak with a high-pitched Kentucky drawl.

The well-known 1864 photograph of Lincoln reading to his ten-year-old son Tad was the immediate inspiration for Mr. Lincoln Sits for His Portrait. In recent years, that photo has become emblematic of the importance of reading to our children–and to that extent it directly links Mr. Lincoln to my longstanding interest in children and their books. My story touches on Lincoln the literacy-minded parent as well as more broadly on Lincoln the master storyteller and writer for the ages. I can only guess about this, but I think he and Ursula Nordstrom, Margaret Wise Brown, and Norton Juster would have all gotten along famously together, if only because they shared a similarly sly and playful sense of humor!

In addition to being a superb writer, something else that Lincoln had in common with my previous “subjects” is that he was a born innovator and an incandescent creative spirit. He was ahead of almost everybody in recognizing the still-new technology of portrait photography as a powerful tool for persuading Americans that he was prepared to lead a nation in turmoil. He was the world’s first commander-in-chief to direct a war remotely by telegraph–the nineteenth century’s new-fangled instant messaging platform. He answered much of his own mail so that all Americans would feel that he was their president, too. A master of symbolism and political theater, he directed workers to speed up construction of the long half-finished Capitol dome, saying that to do so would show the world, at a time when many people had their doubts, that the government in Washington was capable of completing whatever it started.

BB: Was there, at any point, a thought of making this a book for older readers, or was its intended audience always kids from the get-go?

LM: I always saw this as a book for young readers because I remember how much I loved the books about Lincoln that I read as a child and wanted to bring a more contemporary point of view to that literature. As I said before, though, I’ve also done my best to have this book work well for adult readers, too, bearing in mind W.H. Auden’s wonderful observation that “there are no good books which are only for children.” My research is as solid as I could make it and I think I have even made one or two “discoveries” that will surprise even the best-read Lincoln scholars and fans.

BB: Lincoln’s presence in works for children ebbs and flows over the years. There have been, in recent memory, years when not a single picture book or middle grade work of nonfiction came out with him as the subject matter. There are also times when multiple books would be released in a single year. What accounts for his continual presence on the page? Can we ever have too much or too little Lincoln?

LM: Can we or the young people we care about ever have too much of one of history’s best exemplars of wise and courageous leadership? Moral clarity and compassion? The healing power of laughter? Lincoln had all these qualities in spades, and more. As I was reading and writing about him, I found, as so many other biographers have done, that Lincoln is the best of company. To know Lincoln is to feel the urge to spread the word about him.

BB: It is perhaps not a coincidence that the best known informational book on Lincoln for kids is arguably Lincoln: A Photobiography by Russell Freedman and, like this book, its focus is on both Lincoln and the self-marketing of Lincoln through the new photographic medium. Photography plays such a large role in any public figure’s life and Lincoln seemed to grasp that from the start. To what degree does your book tackle this aspect of his political savvy?

Russell Freedman, who I was lucky enough to know as a friend, and who had more than a little of Lincoln’s own plain-spoken wisdom and charm about him, made mention of Lincoln’s prescient awareness of photography’s powers of persuasion in his wonderful book, and he pioneered in the use of archival photos in historical nonfiction for young readers. But I wouldn’t say that he made Lincoln’s preoccupation with photography a major focus of his Lincoln biography, which is essentially a beautifully crafted, traditional birth-to-death narrative.

I’ve tried a different approach, providing a sidebar chronology, but mainly zooming in on certain key decisions, discoveries, and events from the years leading up to and including Lincoln’s presidency. My goal was to give readers a ground-level view of Lincoln as he came of age as a national figure and learned to wield the immense power of the presidency during a time of extraordinary uncertainty and promise.

I brought together many of the most telling photos of Lincoln to show how he morphed over time from an antsy, reluctant sitter into a savvy collaborator with Mathew Brady and the other leading portrait photographers of his day, and how newspapers, magazines, and commercial hucksters of every stripe disseminated his image far and wide, just as the pastime of collecting photos of famous folk was becoming a national craze. It was the beginning of celebrity fandom! And it was also a step forward for democracy because, for the first time ever, ordinary people could have uncannily realistic likenesses made of themselves for sharing with their loved ones and friends.

BB: What do kids not usually know about Lincoln that you’d like them to take away from this book? And did anything surprise you about him in the course of your research?

LM: The backstory I uncovered about the photo of Lincoln and Tad led in many surprising directions, and the result, I think, is a portrait that brings readers closer than usual to Lincoln the caring, funny, shrewd, and sometimes haunted man behind the black suit and stovepipe hat.

One big surprise was how easy it was in those days to meet the president. All you had to do was show up first thing in the morning at the White House entrance, and if you passed muster with the president’s secretaries, you would be granted an audience with the man his assistants affectionately called “The Tycoon.”

Another surprise was how fast and effective communication already was long before the advent of TV and the internet. If Lincoln made a speech in some out-of-the-way small town, his words would be recorded verbatim by a stenographer, then telegraphed to newspapers across America for publication. A mere day or so after an event, everyone in the country who could read would know exactly what the president had said.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I would like young readers to know that Lincoln trusted his own ideas and intuitions and stuck tenaciously to them even when his critics called him all sorts of terrible names. One example of this was his decision, at a particularly difficult time during the war, to invite an artist to spend several months inside the White House while creating a larger-than-life history painting inspired by the Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln loved being around creative people, and the painting that resulted from this offbeat arrangement went on to play an important role in winning Congressional approval of the Thirteenth Amendment, which finally abolished slavery throughout the United States. Having an artist underfoot at the White House turned out to be a very smart move, as Lincoln knew it would all along.

BB: Finally, can we hope to see more books along these lines from you in the future? What’s next for you?

LM: Yes, I do hope and plan to write more books like Mr. Lincoln. It’s not quite time to talk about the next one, but as soon as it is I will be sure to let you know! Meanwhile, my very next book is going to be a hefty and wide-ranging artbook that Abrams will publish in the spring. It’s called Pictured Worlds and is an international history of the illustrated children’s book. It is a project that was a long time in the making and it represents a culmination of years of learning about how an interest in children’s books has spread around the globe, oftentimes through books that we don’t usually get to see here. Writing this book was an eye-opening and world-expanding experience for me and I hope it will be that for readers, too.

I’d like to thank Leonard for taking the time to talk with me today. Many thanks too to Tatiana Merced-Zarou and the folks at Macmillan for setting this interview up in the first place.

Mr. Lincoln Sits for His Portrait: The Story of a Photograph That Became an American Icon is out in bookstores and libraries everywhere starting today. Check out the book that Kirkus called, “A fresh angle offering yet another reason to regard Lincoln as our presidential G.O.A.T.”

Filed under: Interviews

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Finding My Own Team Canteen, a cover reveal and guest post by Amalie Jahn

ADVERTISEMENT