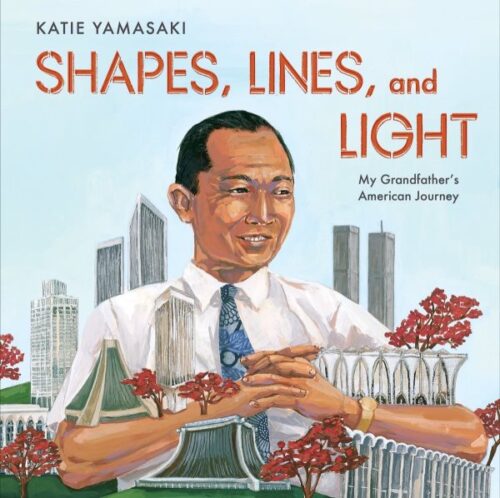

Shapes and Lines and Light: A Katie Yamasaki Interview

As I might have mentioned the other day, the Evanston Public Library recently selected the 101 books for kids published in 2022 that now grace the 101 Great Books for Kids list. It is mighty difficult to cut down hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of legitimately fun books for children down to a measly 101 titles. And you know what book managed to make it onto the list? None other than Katie Yamasaki’s remarkable picture book biography of her own grandfather, Shapes, Lines and Light. Not long ago I had the pleasure to recommend it on TikTok alongside another fabulous picture book about fellow great architect, Paul R. Wiliams. This book focuses squarely on Minoru Yamasaki and I had the pleasure of getting to talk to Katie Yamasaki about her latest title.

Betsy Bird: Katie! I’m so grateful to talk to you today. SHAPES, LINES, AND LIGHT is one of my favorite books of 2022. I’ve seen autobiographical picture books before but I’ve rarely seen cases where the book creator’s ancestor was celebrated in such an affecting manner. When did you first get the idea for the book?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Katie Yamasaki: Hi Betsy, thank you so much. That means so much to me! I honestly have been trying to write this story for literal decades. I first did a bio of my grandfather when I was in 3rd grade. As a kid, I grew up very aware of his amazing accomplishments, but I didn’t really understand the context in which he was formed. I did know, however, that we lived in a very anti-Japanese part of the country (car country, Detroit area), but that he was also very famous in Detroit. Kids would ask me if my grandfather was a kamikaze pilot. Other kids knew he designed the WTC. My childhood was filled with a combined fascination/confusion about who he was and what that meant in the context of the anti-Japanese climate of our area.

I was in my first week of grad school (MFA Illustration at the School of Visual Arts) on 9/11 and all of a sudden, people started saying gross things to me like, “you could get published if you do your grandpa’s bio now.” By that time, I had come to understand much more of the complexity of his life story, but I wanted to distance his biography as much as possible from 9/11. It was powerful watching something he created become a piece of pro-war propaganda, for a war none of us believed in, and I wanted to get as much distance from it as possible . . . So, the long answer is that I’ve had this story on my mind for as long as I can remember. I don’t think I was ready to tell it until now and I also wanted to make sure that there was space for him to be known for the true spirit of his work and his story. For so long, he’s been most known for work that actually least defines who he was as a human and as an artist. But with all these years since 9/11, and a different societal openness for listening to AAPI history, it’s a good time for his story to reach young readers.

BB: In researching the book, how much was done in-house with family members and how much required you to look at outside sources?

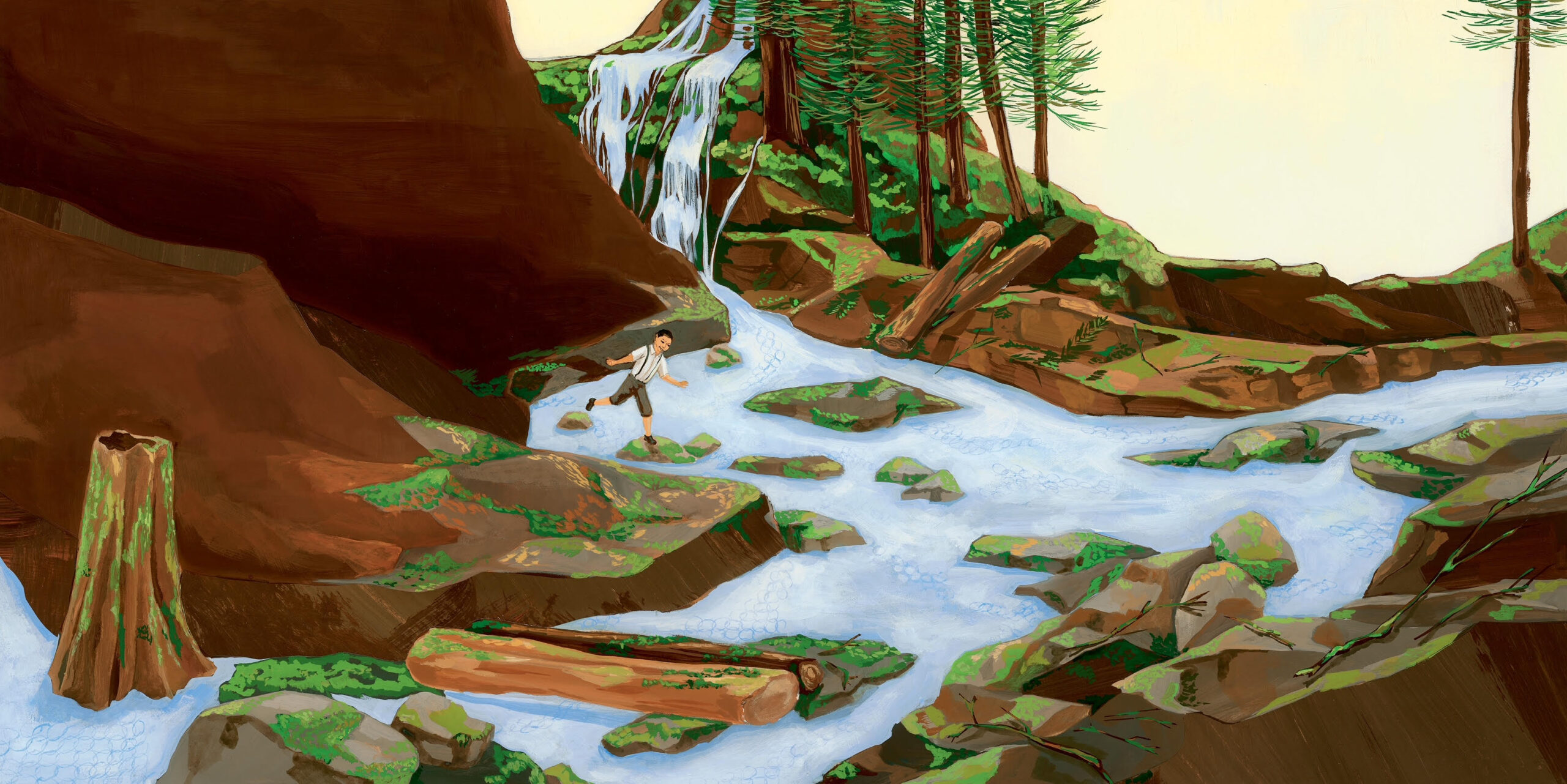

KY: This was a tricky challenge. As you can imagine, our grandfather had a big life and everyone in the family had their own complex experiences with him, stories that evolve and deepen with age and wisdom. We have a big, closely knit family and I really wanted to make sure that this picture I was painting of him felt true across the family. So, I spoke, at length, with the extended family and my main goal was to get at the essence of him and his work as an artist, an architect. My father, the youngest of his three children, also worked with him at his architectural firm, and he was an amazing resource of old stories both from the family side and from the work side. I think that better than anyone else, my father understood my grandfather’s intentions when it came to his work and his life, which I always find so helpful when trying to understand an artist. I also connected with authors of adult/architectural books about him- Dale Gyure and Justin Beal in particular, who were a wealth of unbiased historical information. Their books were incredible resources, as were a few other books. I also relied heavily on Densho.com, an incredible online archive of Japanese American history, based in Seattle, my grandfather’s hometown. My favorite resource, however, is my grandfather’s own book, “A Life in Architecture.” He wrote at length both about his personal journey and his philosophy of architecture and design. It was wonderful to have words directly from him. In his writing and in the best of his architecture, he was guided by humanism and was a very emotive creator and that helped guide the spirit of the book.

BB: Your book FISH FOR JIMMY was inspired by a true story, and the biography HONDA: THE BOY WHO DREAMED OF CARS was a picture book bio that you illustrated. Even so, this is the first book that you’ve both written and illustrated yourself that’s nonfiction AND it’s such a personal story. What was your process in putting it together?

KY: I am a very long-term thinker. When I look back, I think I have been gathering these stories and this understanding of our grandfather for most of my life. In recent years, I’ve been trying to figure out ways that our art could live on the page together, as we are really different kinds of artists. I didn’t feel in a rush to get this book out to the world, but once it was actually time for this book to be made, it was a really intense process. By far, the hardest book I’ve ever made. It’s a big picture book, with a lot of art and a lot of information, but also presented in a kind of spacious way, which means more spreads. More time, and I was working on it in the thick of the pandemic, while parenting a young child and dealing with all the disruptions from Covid school closures, etc. When I was in the thick of making the art, our country was experiencing a new wave of anti-Asian violence. I had been listening to the audio version of Paula Yoo’s breathtaking book about Vincent Chin. My aunt, my grandfather’s oldest daughter, passed away. It was all in the midst of working on this book. It was a lot. The grief of that time was abundant and acute and the story of my grandfather was evocative for me and for others in our family. My studio was wallpapered with images of his buildings, his life, old family photos. My mind was full of his story. And it felt like the awful parts of Asian American history were just playing on repeat on the news every day. It was really hard. But I have this little altar in my studio where I have photos of beloved people who have passed on. So every morning, when I would get to the studio, I would sit there for a couple of minutes and ask them to join me. All my grandparents. My aunt. My infant son who we lost in 2016. And somehow that helped. Because this story certainly isn’t just my story. It’s my whole family’s story. In many ways, this story also belongs to the Japanese American community and the Asian American community. So I would ask for help in working on it and I felt supported. I hope that the book feels uplifting. He went through so much to be seen, to create these spaces where people could feel fully human. He knew what it was to be made to feel invisible and I think the hardship of his life story was painful to retell because I can see, from my vantage point in the family, how these things are passed through generations. But I hope that in the retelling, in the art, the reader will be able to see themselves and their own stories made visible.

BB: One of the struggles that comes with any picture biography is the balance between showing the person in the best possible light and showing the flaws that made them human. You do a particularly excellent job of at least touching on your grandfather’s triumphs as well as the things he was criticized for. How do you walk that line?

KY: When I was figuring out the approach for this story, this was one of my biggest challenges. Certainly, if this was a book for adults, it would be very different. There are details about his personal life that I chose to leave out. Ultimately, I decided that the facts of his life that would make it into the book were the details that helped the reader best understand the work he was trying to make. The hard and the glorious personal details of his history that led him to design these humanistic, aspirational spaces. He had a textured personal life, that I know was largely influenced by poverty, racism, and growing with a need to be seen and prove his humanity. While trying to figure out what to leave in and exclude, my guiding thought was, what will best help the reader understand the essence of who our grandfather was and what his work was intended to do. It’s impossible for me to separate his personal flaws and challenges from his life, from the context that he was raised in. From this notion that as a poor, Asian man, his life had no value. That is how he was made to feel. So, when I am taking this book around, what I am focused on is talking to young readers about the inherent value of their own lives. That they don’t have to build the biggest, run the fastest, score the highest for their lives to have value. Their lives have inherent value for the simple fact of their existence. To, when thinking about your life and your future, to begin there. And then you will have your daily struggles of everyday life, but the burden of proving your humanity, as our grandfather did (often to his own detriment), will not be a part of that journey.

BB: I think it’s in the backmatter that you mention what a storied and celebrated family you come from. Have you ever felt a particular push to succeed in light of your relatives’ accomplishments, or has that not really ever been the case?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

KY: Definitely, there is some insane accomplishment in my family. But my family is huge on both sides and there are also very wonderful, very grounded teachers, nurses, social workers, postal workers, engineers, park rangers, musicians, and every other kind of worker in my family, so the high achieving artists weren’t the only model. I am actually a 4th generation teacher on my mom’s side. My parents are VERY different than my grandparents on my father’s side. They were back-to-the-land hippies and we were raised more in that kind of community than in a pressurized achievement-based way. My father really understood, from a first hand experience, the cost of that kind of drive. Our grandfather used to say to him, my aunt, and uncle, “Why be the best in the world when you could be the best in the history of the world.” Lucky for us, my father rebelled from that kind of thinking and our parents raised us to be focused more on doing work that had meaning, less on accomplishment. But for me, I just saw those achievements and thought, art is not for me. It was too much pressure to achieve in a certain way. And because of that, I had a relatively late start to art- I didn’t really learn how to draw until I was in my early 20s. I think by then, I had a good enough sense of myself, and some incredible teachers, who helped me find my own path that was really different from that of my grandparents. I also never felt that kind of invisibility that they grew up in, and so I never felt the drive to prove my worth. That would have been a burden that would have had terrible consequences on my work and lifestyle in general. I have a lot of drive, but for me the drive is to get stories out that feel like they are shining a light on the margins. I especially feel that way about books like Dad Bakes and my new book for 2023, Place Hand Here. These are books that focus on families who are impacted by incarceration and I have a feeling that the sooner people can see one another more clearly, the better for all of us. That’s where my drive comes from.

BB: Finally, I love the author photo of you in this book which shows you standing beside your grandfather, watching him write or draw. Was that an easy photo to find or did you have to dig through a couple albums first?

KY: My aunt Carol was a glorious photographer. She passed away while I was working on this book, and after she passed, we all spent a lot of time looking through her photos. I found this in one of her albums, she had taken the photo and it felt like one more gift from her. I hope she would have liked the book if she had lived to see it.

For fun, be sure to watch Katie discuss her book on video here as well:

Many thanks to Katie for taking the time to answer my questions.

Random Fact: After my TikTok video premiered my mother, who grew up in the Detroit area, wrote me the following note about Mr. Yamasaki:

“…. and I just check, and yep, his office was near us when I was a kid – AND two guys I went to high school with, assigned a humanities paper, walked into his office and asked to interview him and he let them!”

Thanks too to Caroline Sun from Sun Literary Arts for setting the interview up. Shapes, Lines and Light is on shelves everywhere now.

Filed under: Interviews

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

More Geronimo Stilton Graphic Novels Coming from Papercutz | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

ADVERTISEMENT