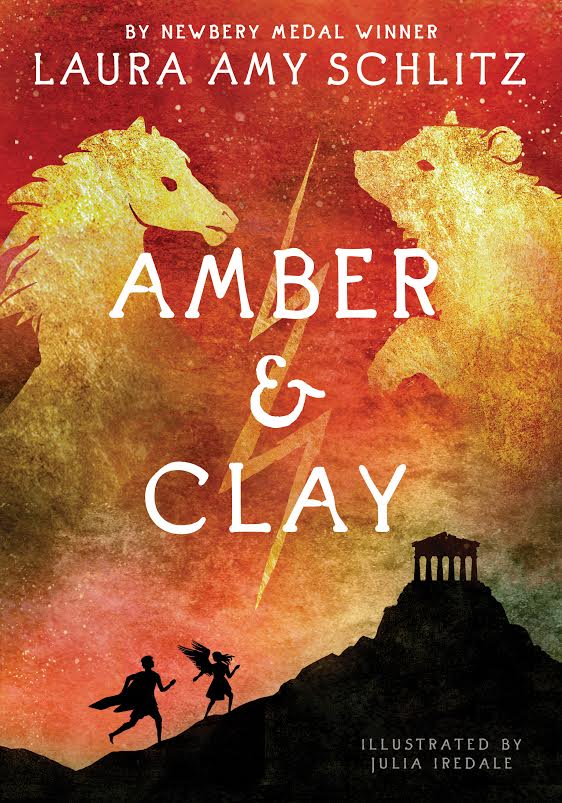

Review of the Day: Amber and Clay by Laura Amy Schlitz, ill. Julia Iredale

Amber and Clay

By Laura Amy Schlitz

Candlewick Press

$22.99

ISBN: 978-1-5362-0122-2

Ages 10-14

On shelves March 9th

“Hermes here. The Greek god – / Don’t put down the book – / I’m talking to you. If the lines looks like poetry, / relax. This book is shorter than it looks.” He may be the god of liars and thieves, but here’s one moment when Hermes is telling the truth. Funny story. I remember working as a children’s librarian in New York City when, one day, I got “that kid”. Librarians, you may have had “that kid” in your rooms as well at some point. It’s the kid that has read (their words) “everything”. They are fairly certain that you will fail to impress them, so, naturally, you bend over backwards to do so. They want good books, nothing but the best, and if you mention something they’ve already read they are allowed to look upon you, not with scorn, but with pity. In this particular case (and it was about a decade ago) I found that Diana Wynne Jones took care of the problem nicely (they’d never heard of her) but I think about that kid periodically over the years. And when I encounter a book that is of high literary quality, they sometimes come to mind. Yet the thing about Amber and Clay, by Newbery Award winner Laura Amy Schlitz, is that while it would have been the perfect story to hand over, it isn’t just for “that kid” at all. A verse novel at its core, this is a book for those Percy Jackson fans. For the kids that like their fiction realistic, but don’t mind the occasional Greek God butting in for effect. For kids that like historical fiction with loads of accurate details (you’ll never forget what a strigil is). For kids that like verse novels, since they look so impressive and read so much more quickly than you might expect. This is a book positioned to impress, that then sneaks over and steals your heart. Hermes would be proud.

Two children find their fates linked, but not at the beginning. On the one hand you have Rhaskos, born a Thracian slave in Greece circa 400 BCE. His mother loves him, but too soon she’s sold away. Now his only comfort comes in drawing horses in the dirt, and what good would that do him? On the other hand you have Melisto, born wealthy and privileged, but with a mother who hates her and a father that’s often gone. When she is selected to be one of the special daughters of noblemen who will be a bear for the goddess Artemis at Brauron she finds a happiness she’d never encountered before. Rhaskos loves horses and Melisto comes to love a bear, but things change for both of them, and along with the philosopher Sokrates, their lives will soon be impossible to separate.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

You can admire a book’s writing, but not love its characters. This, while unfortunate, happens when an author is being too clever by half. Yet what I found with this Laura Amy Schlitz novel was that embedded deep in the text was one of the smartest methods I’ve seen an author use to connect an audience to characters. At the outset are the obvious narrative techniques (parceling out information about the past (exposition) is much easier when you’ve a god to do the dirty work). And then there are the risks. If you should find yourself simultaneously attracted and repulsed by elements of this book, I shouldn’t think that was a coincidence. As I read it, I was very much taken by the ways in which Schlitz continuously pushes and pulls at the reader. Consider how you first encounter the story. The very first thing you see (after the cast of characters, of course) is “Exhibit 1” It’s a fragment of a broken pot, much as you might see in a museum. Indeed the description of this object is contemporary, speculating on its creator. Then you are drawn closer by the charm of Hermes himself. He tells you a story. Then you are Melos, being addressed by Rhaskos. Could anything be more intimate? You are one of the central characters of the book, hearing the story from the other main character’s point of view. Do you see how the book takes you away initially and then pulls you in? The moments where you see the past as merely a series of objects distances you. Then you’re pulled into the first person again. Away and in. Away and in. And in this motion of away and near Ms. Schlitz draws you closer and closer to the characters’ hearts. Did I happen to mention that she’s also writing all this in verse? Blank verse and strophe-antistrophe (or, as she prefers to call it, turn-counterturn). There’s some datylic hexameter, elegiac couplets, and even a character speaking in hendecasyllables. But always the form matches the personality of the character that wields it. These choices, rendered in a book for kids, should distance you, yet you’re only more interested in the hearts and minds of the people you have come to know.

Why you come to a Laura Amy Schlitz book is your business. Me? I come for the writing. More specifically I come for the descriptive writing. Some choice examples:

• Upon discussing Greece: “it’s not a land / that feels that it owes you a living. The soil / is laced with acid and iron. The country / has always been poor.”

• “Plague is disgusting / and tedious, too.” (I really felt that one this year)

• “If he couldn’t win, / he was like a drunkard without drink.” (hmmm. That one too.)

• “She knew her mother was an attractive woman, but there was something feral about Lysandra’s grace, something that reminded her of a weasel she had once watched kill a snake.”

• Of the bear, “Whatever it felt, it felt with every cell in its body. There was no moderation and no fraud.”

• “You must have seen what I saw that day – / stone that glows like honey through cream.”

• “He stood like a statue, not weeping. / I know what it is not to cry.”

• And even the child that is convinced that they know everything that has ever been written about the Greek gods may find that Ms. Schlitz writes little elements you never thought through before. Lines like “Artemis, the only Olympian goddess who had ever been a little girl” can catch you by surprise.

Indeed any author who casually throws out a line like “O, the wine-dark sea!” is working with some references (eat your heart out, Iliad). A look at the Bibliography shows a whopping forty-three sources. Surely these became useful in the course of things. If nothing else, they may have inspired the different ways in which the book is written. I don’t even know all the poetic forms Ms. Schlitz is working with here. There’s a section where Rhaskos has created a very decent clay pig. The text bounces between his thoughts and those of Hephaistos, who is rather charmed by the boy’s accomplishment. Many of the lines in the Hephaistos section (“the pig is good”, “Like Prometheus…”, “a world from clay”) are repeated, after a fashion, in the Rhaskos part (“… the animals were good”, “I felt like Prometheus…”, “who made mankind from clay…”). Does it mean something? Hmmm.

In her Author’s Note at the back, Schlitz makes it clear that she cannot correct the sins of the past. We see today the horrors of slavery, no matter the era, but in this book even the kindest most intelligent man there doesn’t critique it. Schlitz notes that she couldn’t put words in Sokrates’s mouth on the matter. Indeed, even Rhaskos mentions early on in the text, “He didn’t know how bitter it is to be a slave. / He couldn’t see that it was wrong / that I was a slave. He was the wisest man in Athens, but he couldn’t see that I’d been wronged.” Rhaskos can see the problem with his time period and say that it’s wrong because it affects him directly. What about when there are moments when Rhaskos himself is in the wrong? Every historical character is a product of their age. To what extent do you allow them to discuss their own prejudices? Generally speaking Schlitz keeps Rhaskos on a tight leash, but once in a while he falls prey to the era. He calls the men that use a less respected gymnasium, “Foreigners and half breeds, metics, human mongrels,” only to find the wisest man in Athens there having scintillating conversations with them. We cannot escape our age. We can only hope to dodge it a little.

Mind you, this is not the only time Rhaskos is unlikable. Indeed, Schlitz takes a chance on making him downright nasty for a while. When he first goes to work for the potter Phaistus he’s awful to both him and his wife Zosima. The risk here is evident. Should the reader turn on Rhaskos for his behavior, they will not want to read the book any further. Thankfully, Rhaskos is written in the kind of first person narrative that manages to be understandable but not sympathetic. And maybe some folks will find him too much of an adolescent, but at least you’ve been with him a long time before these sections. You want to see him come through it all in one piece.

I’m a children’s librarian by training so I cannot read a book like Amber and Clay and not pair it with books already in my library. Indeed, as I read, the connections started to come faster and faster. Let’s see, let’s see . . . obviously with Hermes starting the story in the way that he does you’d want to make sure a kid was up on his “Olympians” series of graphic novels by George O’Connor (particularly any pertaining to Hephaistos and Hermes). And why not throw in I Am Hermes by Mordecai Gerstein for spice? It may read young but the info is good. The overall realism of the text of Amber and Clay (with the exception of the occasional god popping up here and there in the chorus) brought to mind the Newbery Honor book The Winged Girl of Knossos (a gender swapped and researched retelling of the Icarus myth). Next you have the fact that much of this story is about a boy who works for a potter and there is a distinct possibility that the apprentice may be remembered long beyond the master. Sounds like A Single Shard by Linda Sue Park, yes? And the bear? The bear that Melisto comes to love? If that bear does have at least a little kinship to the bear in Frances Hardinge’s A Skinful of Shadows then I don’t know my job.

Recently I’ve been trying to put a name on that feeling I sometimes get when I’m reading a book for kids and become suddenly overwhelmed with this sense of relief that the writing is as good as it is. Is there a word for that? Probably in some language out there. I can’t guarantee to you that you’ll have the same feeling, but I can say that while this book may look intimidating, and many of the words I’ve written here may make it out to be some kind of lofty, classical text, this is just a plain good story. A boy. A girl. Horses and bears. Philosophy but the kind you actually want to read more of. Bullies. Lightning strikes. Ghosts and death and daimons. Read it aloud or hand it to a young reader. Whatever you choose to do, find it a home. There really has never been and may never be a book quite like it again.

On shelves March 9th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2021, Reviews, Reviews 2021

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Finding My Own Team Canteen, a cover reveal and guest post by Amalie Jahn

ADVERTISEMENT