Working in Translation: An Interview with Editor-at-Large Louise May

Folks, I know you’ve been hearing an awful lot of interviews this week, but we simply are not through! You see, recently it occurred to me that when it comes to bilingual picture books, there is a kind of art to their design. To place two languages on a page and have the end result look beautiful and memorable is, quite frankly, a wonder. And some of the best of these bilingual texts comes out of none other than the publisher Lee & Low. Knowing this, I set out to find out WHO precisely was responsible for these book. My answer was none other than editor Louise May. Today, Ms. May sits down with me to discuss some of her titles and how they came to be.

Betsy Bird: First and foremost, I’d love to hear a little bit about your own background. What led you to your current position as Editor-at-Large at Lee & Low Books? And how did you begin to have an interest in bilingual books for kids?

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Louise May: I started out in educational publishing many years ago, editing textbooks. At that time, there was a growing movement toward more equal representation of women and people of color in prominent roles in both text and art, which started me on the path to embracing and championing diverse children’s literature. From purely educational publishing I moved to a company that published diverse books for both the educational and trade markets. Then, almost twenty-two years ago, I joined Lee & Low, a trade publisher that also has a strong presence in the educational market. It was at Lee & Low that my interest in Spanish editions and bilingual books began as the company grew and endeavored to provide diverse literature for Spanish speakers. At first we published mostly separate Spanish editions, but with the acquisition of Children’s Book Press in 2011, our commitment to bilingual books expanded exponentially as we saw how popular the bilingual CBP books were among our customers. We began publishing more bilingual books, especially those with Latinx content and by Latinx creators. I was immediately drawn to the challenge of creating beautifully designed bilingual books. I love designing books almost as much as I love editing them, so making lovely books that embrace text in two languages was right up my alley.

BB: Could you tell us a bit more about what bilingual books for children mean to you, personally? And how do you see them being used in the wider world? What are their advantages and uses? When do you feel they are used best?

LM: To me, bilingual books are an invaluable tool to expand children’s awareness beyond themselves, regardless of which language is their dominant one. It is also important for children to see themselves represented in the stories they read, and bilingual books that give equal weight and prominence to both languages promote a sense of belonging in children, of not being othered. In the wider world, bilingual books promote understanding in an environment where all languages—and children— are valued equally. Bilingual books can help children master a second language more quickly by supporting and cultivating language skills. Children read in their stronger language while also learning vocabulary and sentence structure in the second language. Well-written, engaging, beautifully illustrated bilingual stories help children develop a love of reading. We all know that children love to read or hear their favorite stories over and over again, and bilingual books increase literacy by providing for this in two languages.

I think bilingual books are used best in any supportive environment—at home, in school, at the library. Because of their benefits for language acquisition and literacy growth, bilingual books have the greatest impact with younger children who are developing and acquiring these skills. But I would not rule out that bilingual books can be enjoyed by and informative for readers of any age!

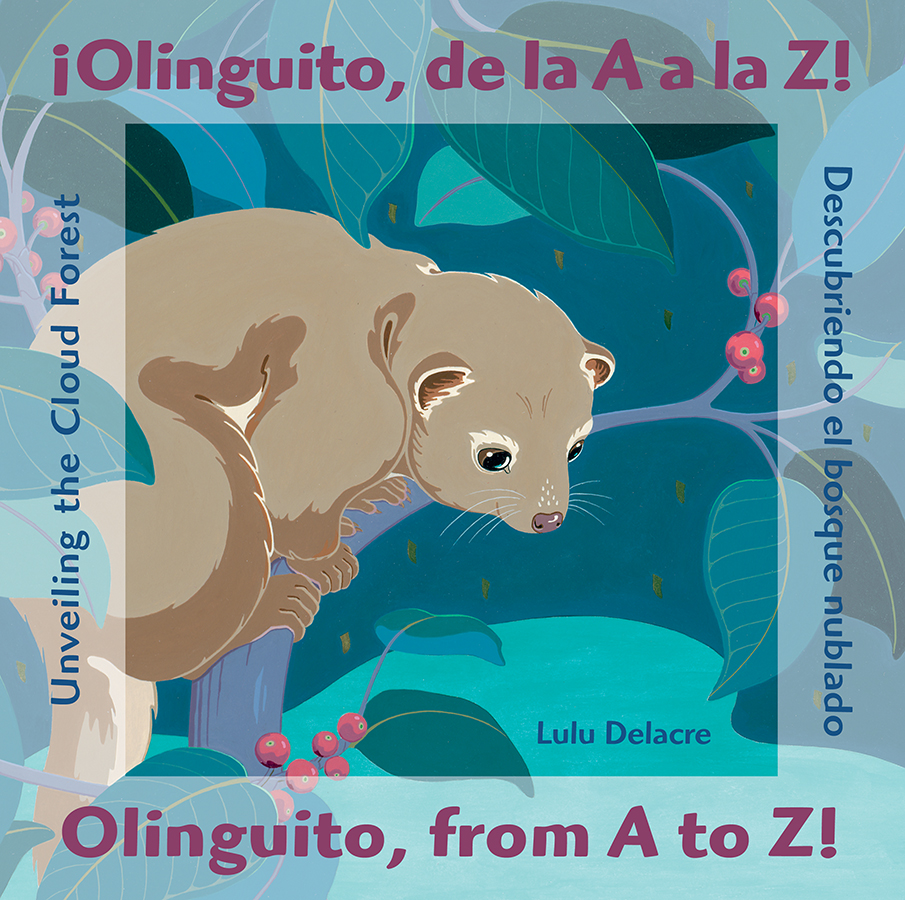

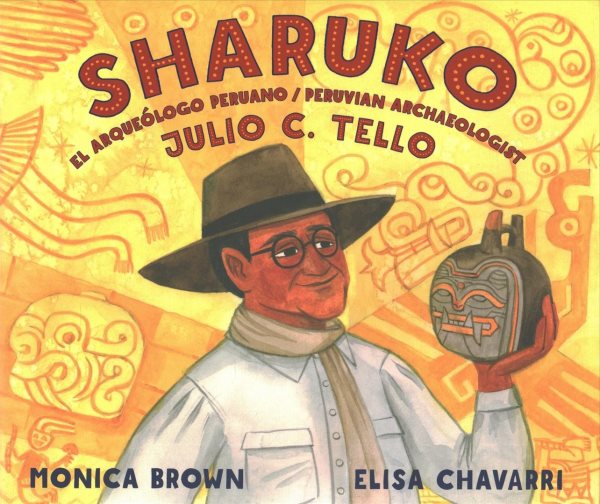

BB: One of the reasons I wanted to talk to you has to do, in large part, with the innovative ways in which the bilingual books that Lee & Low produces are presented. I’m thinking specifically of OLINGUITO A TO Z as well as 2020’s picture book biography SHARUKO. The sheer design of these books is a delight to the eye. Who is responsible for that design? Does that person work with the author? Is the author consulted at all about the way in which their words will be presented on the page?

LM: I believe a bilingual book should be as beautifully designed as a book with text in only one language. As with all picture books, designing a bilingual book is definitely a collaborative process among the illustrator, art director/designer, and editor, and also sometimes the author. The main thing that is different for bilingual books, though, is that the design and image compositions must allow enough space for the text in both languages to have equal weight, importance, and breathing room on each spread. This is something the editor and art director/designer have to make sure the illustrator is conscious of right from the beginning, through all the rounds of sketching and finally the creation of the finished illustrations.

Each book has its own path to publication, and the two books you mention above developed in different ways. Lulu Delacre, the author and illustrator of ¡Olinguito, de la A a la Z!/Olinguito, from A to Z!, also has a graphic design background, so she came to me with the design of the main part of the story pretty much figured out. Plus, she has been creating bilingual books for many years, so she knows how to make sure the all the text and illustrations work together seamlessly. When someone is both the author and illustrator of a book, they usually develop the text and art in tandem, which often makes for a smoother integration of the two.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Sharuko: El arqueólogo Peruano Julio C. Tello/Peruvian Archaeologist Julio C. Tello by Monica Brown and illustrated by Elisa Chavarri, was approached differently. As noted above, the text in both languages had to be accommodated right from the very first sketches. Usually, we have only the English text at the start of the illustration process, so the designer sets the English text twice on each spread, often with an extra line or two added in the text that represents the Spanish because Spanish text often runs a little longer than English text. This is how we proceeded with Sharuko. The illustrator was then free to move the two text blocks around on each spread to accommodate her compositions, and we made sure to vary the placement of the text blocks and illustration layouts among the spreads to encourage visual engagement with all parts of each spread. The illustrator, art director/designer, and editor all work together in an organized path of communication. Each person offers ideas and feedback until everyone is pleased with the final sketch. And as with any book we publish, the author is sometimes consulted, to ensure authenticity, and that was the case with Sharuko. We were all struggling with one particular spread, until feedback from the author helped clarify what needed to be shown, and how.

BB: Do you have any particular pet peeves regarding assumptions about bilingual books?

LM: Adults who speak only English sometimes are leery of bilingual books because there is a second language on the pages that they cannot read. They claim the child/children they have in mind for the book don’t need the non-English text; that it is unnecessary or could be a distraction. They fail to see or understand the benefits of bilingual books that I’ve noted above.

BB: And finally, where would you like to see bilingual literature for children moving in the next few years?

LM: Currently most bilingual books published in the United States have English and Spanish text. I would like to see more bilingual books for other languages—Arabic, Chinese, Korean, Russian, Vietnamese among them. There is a huge population of children in the US who come from homes where English is not their first language, so the opportunity to represent these children’s worlds by publishing more bilingual books is there for the taking.

Thanks once more to Louise May for speaking to me today. Thank you too to the good folks at Lee & Low for putting out these fantastic books. For yet another interview with Ms. May, please check out this Editor Interview, conducted by Cynthia Leitich Smith.

Filed under: Interviews

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Finding My Own Team Canteen, a cover reveal and guest post by Amalie Jahn

ADVERTISEMENT

I was impressed with the placement of the English and Spanish text in Sharuko. I wondered about the Indigenous text since Spanish is the language of the conquerors. I appreiciate learning more about Louse May and the process for these texts. i hope to see more of them.

That is an excellent point. And there was a critical review of the book posted on a blog earlier this year that I tried to find. Unfortunately it doesn’t come right up in a Google search but it questioned not the use of Spanish (which is an excellent point) but the questions surrounding the very nature of archaeology itself. If anyone could find it and post the link here, I’d be grateful.