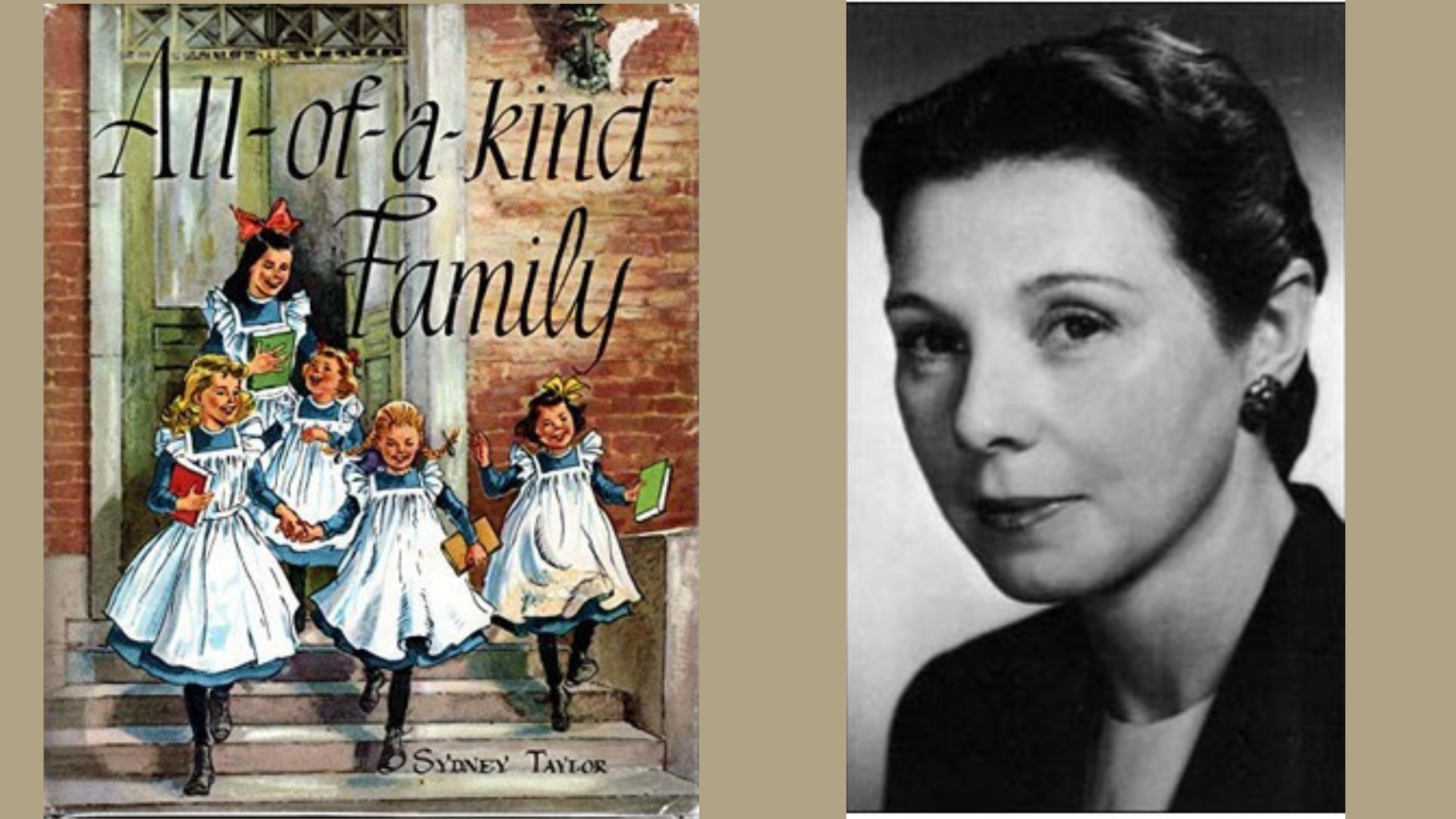

Review of the Day: Climbing Shadows by Shannon Bramer, ill. Cindy Derby

- Climbing Shadows: Poems for Children

- By Shannon Bramer

- Illustrated by Cindy Derby

- House of Anansi Press (an imprint of Groundwood Books)

- $18.95

- ISBN: 978-1-77306-095-8

- On shelves now

I don’t think I know what poetry is anymore. I think once upon a time I used to, but the definition was cold and stark and not particularly interesting. I remember the vague attempts of teachers to make it comprehensible in high school (I don’t remember much from elementary school). Really, it’s only when I grew up and started reading children’s books of poetry with intent to review that I began to pick apart what poetry is actually supposed to be. It’s words (words I get) but it’s feelings too, and that’s a harder horse to ride (so to speak). Poetry, when done well, means something to the reader. Now as part of my job, I try desperately to read as many different collections of poetry for children in a given year. A lot of it is pretty standard stuff. Poems about sports. Poems about seasons. Haikus. And then once in a very great while you get something like Climbing Shadows that throws the whole system out of whack. Do you remember that scene in Orlando by Virginia Woolf where a bunch of witty people are in a room saying witty things and then Alexander Pope walks in and says three things so devastatingly witty that he just destroys everything? That’s what happens when Climbing Shadows gets paired alongside other collections of poetry. Smart. Honestly heartfelt. Utterly beautiful to look at. See the bar? Yeah. It just got raised.

When you say a book has “poems for children” you usually mean that it has poems written for a child audience. But in the case of Climbing Shadows each of the twenty poems included was written with a specific child in mind. For the child who loves owls, the poem “Owl Secrets” says “I am old inside my body / Because I know the secrets of owls.” The kid that loves two toy cars introduces them with, “Crashout is all business when he races / Powerdog thinks he can win his older brother’s heart / and make him turn off the TV forever.” But the only poem that includes a specific child’s name is the last. “A Question for Choying”. The poet is to the point. “Are you going to write it down? / You should because sometimes / the poem inside / disappears like a snowflake – / a tiny crystal star / in your shiny black hair / that melts away / nearly before it is seen.” May these poems never melt, never disappear, and never fade away.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I am beginning to suspect that my lunch workers in elementary school were not making adequate attempts to reach their full potential. For years we have been privy to Jarrett Krosoczka’s Lunch Lady graphic novel series with its fishstick nun chucks and spatula-based secret weapons. And now, at long last, it appears that there is a challenger to the Lunch Lady throne. Not a lunch lady, per se, but a lunchroom supervisor a.k.a. the person who is there to open your Kindergartener’s milk carton and make sure that they don’t misplace one of their fuzzy mittens. In her extensive Author’s Note, Ms. Bramer gives us the Climbing Shadows origin story. While working with the kids Ms. Bramer explained that she was a poet (she’s actually won things for her collections, like the Hamilton and Region Best Book Award). The children were a bit baffled (poets don’t turn up in a lot of community worker picture books) so she started reading poetry to them. One thing led to another and for Valentine’s Day she offered to write them each a poem about anything they wanted. “Many of those valentine poems appear in this book … Climbing Shadows: Poems for Children is the result of the wonderful exchange between myself, poetry and children who needed me for a little more than an hour at lunchtime – when we had just enough time to eat a sandwich and more than enough time to read a poem.” Sorry, Lunch Lady. Looks like I’ve a new lunchtime superhero now.

Let’s play a fun game. You pick up this book, read through it, and then tell me the precise moment it won you over. I had to go back and flip through it to find the moment myself. The poem “Skeleton Song” was the one that made my eyebrows raise, ever so slightly. But maybe that was just because I really like skeletons. Moving on, there’s the poem “Three Hearts and No Bones at All” about octopuses. I like science and I like it in poetry, but the poem really reminded me of one that my mother might write (my mom’s the poet behind the collection A Mind Like This) so, again, I might not be a fair judge. I was wavering at that point, so when I came to “I Don’t Need a Poem” I succumbed entirely. It’s this supremely economical poem that says loads and loads in as few words as possible. It reads as if Ms. Bramer was told by a child that they didn’t need a valentine poem, and this is what she gave them instead. Here’s the part that slays me: “I speak Romania / I like Canada / I can’t go home, so / I am going to give my teacher / a flower tomorrow / I am going to give everyone / something from me / It’s okay – I don’t need a poem / I am going to give / something to you.” See that puddle on the floor. That’s me. Please don’t step in me.

All of which gets me to thinking about the why. Why are these poems as good as they are? What is Ms. Bramer doing here that other people do not do? To find the answer, I did something for this review that I try to avoid as a general rule: I read other reviews of this book. Generally speaking I don’t even like to read the bookflap of a book when I write a review, but Climbing Shadows is beyond my abilities. I looked around. In one instance, Jules Danielson in her review at Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast said, “a quiet book is one that leaves the reader room for contemplation. Perhaps it can also mean a book with inherent ambiguities in part or in full, a book that asks more questions than it provides answers.” She’s hitting close to the nub of the matter. Alternatively, the professional reviews from the journals were very disappointing. Only Publishers Weekly delved slightly beneath the surface saying, “The works carry notes of wistfulness and wonder, astute observations, and poignant reflections on one’s place in the world.” The trouble with this wistfulness and ambiguity that they refer to is that I’ve read books that could be described in that manner before but they don’t touch me the way that Bramer’s work touches me. It feels as though she’s able to simultaneously zero in on specific moments and thoughts, but her touch is so light that they are, at the same time, strangely universal. The child reading this book will see themselves in it. Even if the poem is just about a spider.

Cindy Derby is having a bit of a banner year here in the States. A puppeteer on occasion (someday someone should make a definitive list of all the children’s book illustrators that are also puppeteers) her two picture books on 2019 have been garnering all sorts of attention. She will probably be better known for her humorous picture book How to Walk an Ant, out with Macmillan, but for me, this is the book I wanted to zero in on. Here, Derby’s art sort of looks like the lovechild of Stephen Gammell and Matt James. That spidery, delicate art all awash in evocative watercolors that feel like something out of the world’s nicest fever dream. Only Derby could make the hips of a skeleton look like a particularly lovely variety of Venus flytrap. Only she would cover a grumpy girl in anthropomorphic chocolate chip cookies, all feet and boots and crumbs. But the reason that Derby was the absolute ideal person to pair with these poems is that she can do exactly what Bramer does, note for note. When Bramer goes big and expansive, when her view backs up and backs up and encompasses so much more than one child and one thought, that’s when Derby backs up. That’s when you’ll see her snow splattered pines on steep mountainsides and the moon shine on a woman padding down a steep hill one moment and then the wispiest strand of a spider’s web or the shadow of a flower on snow the next. A person should get vertigo the way she moves about from page to page but instead you just feel so safe and comforted. Derby’s art makes you feel that everything is going to be okay. Even when it’s weird. ESPECIALLY when it’s weird.

I don’t think I know what poetry is anymore. And that’s okay. Maybe nobody really knows what poetry is. Maybe poetry is what we do when we find we have to make verbal sense of wordless things. Thoughts like that make me want to write big, long treatises on the relationship between verse and art. Sort of. Maybe it’s better just to hand you this book instead. Unlike this review, it doesn’t go on and on, waxing rhapsodic over an octopus or a birthday party or car. In the poem “You Speak Violets” the poet tells the child, “i see rushing water in your eyes when you get a new idea / sun through the branches making shadows inside you / when you find it hard to say what you are feeling / you speak violets.” These poems speak words. And that’s pretty okay too.

On shelves now.

Source: Borrowed from library.

Other Reviews: Check out this write-up on Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2019, Reviews, Reviews 2019

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

Exclusive: Giant Magical Otters Invade New Hex Vet Graphic Novel | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

ADVERTISEMENT