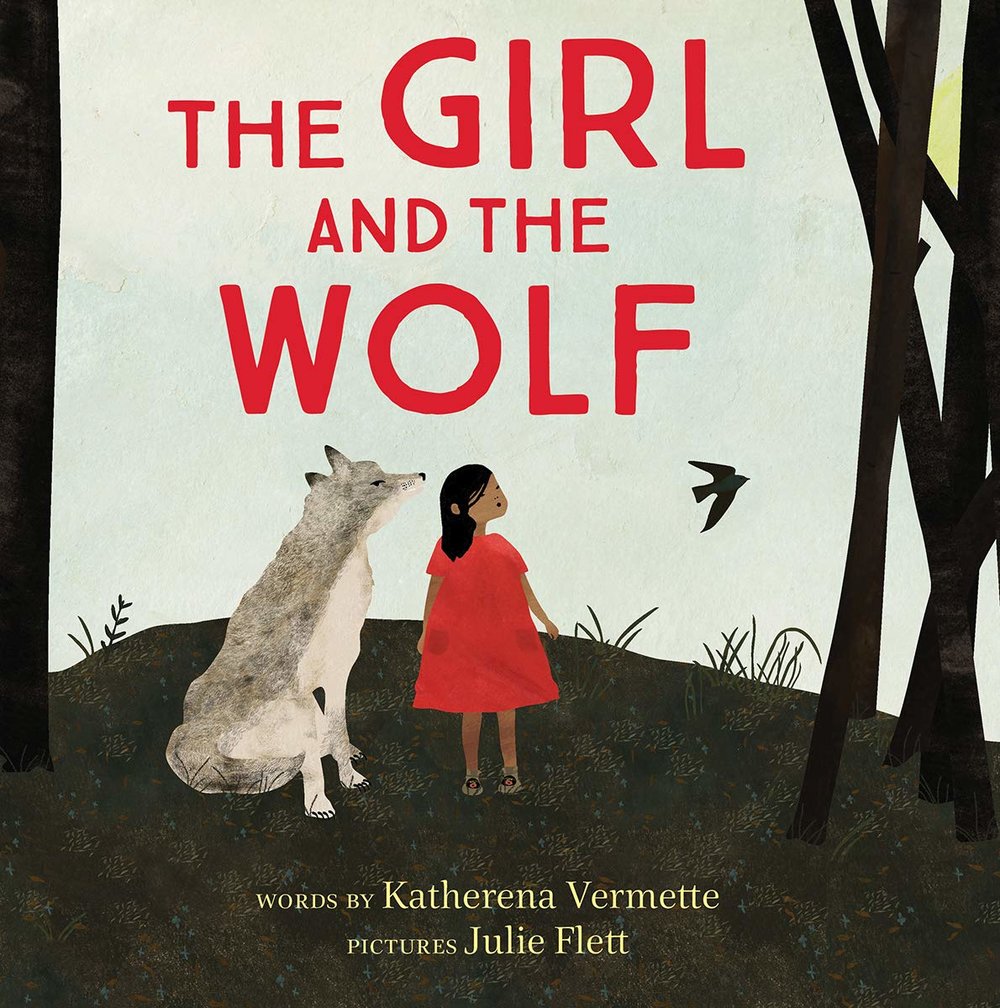

Review of the Day: The Girl and the Wolf by Katherena Vermette, ill. Julie Flett

The Girl and the Wolf

By Katherena Vermette

Illustrated by Julie Flett

Theytus Books

$19.95

ISBN: 978-1-926886-54-1

On shelves now.

There was a time, not long ago at all, when a call for “diverse voices” in a children’s library would have led you to a particular location: The folktale and fairytale section. Many a well-meaning librarian would hear your request for books reflecting the experience of one group or another and direct you to the 398.2s. Why? Because for a long time those were the rare books that even acknowledged that other races, ethnicities, religions, etc. existed in the world. But if you’d followed the librarian’s advice and perused the section, it wouldn’t have taken you very long to realize that the bulk of the books there were written by white people. Before #ownvoices was even a gleam in the public’s eye, white people would merrily write outside their lived experiences without a second thought. Sometimes they’d do the proper research, but a lot of the time it was, to put it mildly, loosey goosey. Nowhere was this more evident than when it came to books about Indigenous spiritual tales. We’re talking appropriation on a pretty massive scale, to say nothing of the fact that, adding insult to injury, they’d be labeled “folktales” to boot. Now walk over to the 398.2s these days and all those books are still there. Fortunately, thanks to efforts by publishing companies like Inhabit Media, Theytus Books, and others, we’re seeing a marked increase in the number of Indigenous authors and illustrators every year. The Girl and the Wolf by Métis author Katherena Vermette and Cree- Métis artist Julie Flett, is one of these; an original fairytale in the purest sense of the term. Essentially, it takes a European idea and flips it on its head. A book that cracks the limitations of the fairy tale form wide open.

While her mother picks berries, a young girl “helps”. Which is to say, runs about as fast as her legs can take her. Forgetting her mother’s advice not to stray too far she soon finds that she has become lost in the woods, and nighttime is descending. To her surprise, a wolf presents himself but he does not seem intent on harming the child. Instead, he asks her questions that get her thinking. “Do you know how to hunt?” “What are you going to do?” When she says she doesn’t know the wolf snaps her out of her self-pity and urges her to take in her surroundings. In doing so she not only finds food to eat, but a way out of her predicament. Soon she is in her mother’s arms once more. Later, she leaves tobacco for the wolf by way of thanks.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

As a young librarian, I was taught some very strict guidelines regarding fairytales. When working on New York Public Library’s annual 100 Books for Reading and Sharing list, I was told in no uncertain terms that books to be taken seriously had to be based on real folk and fairytales and not just something someone made up. Never mind that every story, at its core, is just something someone made up, or that part of the charm of these books is how each author and artist puts their own spin on the proceedings. It was only when I left NYPL that I began to relax my own parameters a bit. As far as I’m concerned, fractured fairytales can get a bit samey after a while, but books where the tale is shifted and seen in a whole new light, THAT is worthy of consideration.

On first glance the biggest difference between this story and any European one you can name is that the wolf is not the antagonist in the tale. That doesn’t mean that Vermette doesn’t play up the danger. The wolf may not be threatening but that doesn’t mean he isn’t wild. The first time he appears he is described as “a tall grey wolf with big white teeth…” When he sniffs the girl, “His wolf breath was hot and stank of meat.” Even Flett plays this up, subtly. Here is an animal, the tips of his teeth visible as he approaches. When it becomes clear that he means the child no harm, the book seems poised to make him into a protector or guardian. Instead, he’s a guide to the child. He provides no answers, only the questions that calm the girl and allow her to think critically. Under his guidance she can feed herself and locate places that look familiar. Their relationship is an empowering one, the wolf helping the girl to clear her head and find her own answers. The wolf is, then, like an ideal parent. Guiding the child but never giving away the answers outright.

Recently I was reading my daughter Louise Erdrich’s novel Birchbark House and we kept coming across instances when characters would give thanks using tobacco in some way. Many is the child of the 21st century that associates tobacco with cigarettes and is repulsed by its existence. And really, until I read The Girl and the Wolf I’d not encountered it in any other children’s titles. In the book, after she is safe home once more, the girl leaves some tobacco in red cloth at a bush’s edge, “Because she didn’t know a better way to say thank you.” In context this could be interpreted, but I liked that Vermette included a note about the tobacco in her Author’s Note at the end. Not only does it explain succinctly tobacco’s role in times of gratitude, but it allows this book to be nicely paired with Erdrich’s. I’m a librarian, so pairing books together is basically my favorite part of my job.

I’ve encountered the art of Julie Flett over the years, but usually when her books make it into the American marketplace they’re in board book form. In The Girl and the Wolf Flett limits her color palette to earthy tones and hues. There are great subtleties to her work, like the gently mottled fur on the wolf’s back, or the silhouette of grasses against a grey/blue sky in the fading light. Because the book takes place at twilight, Flett has to capture the time of day when you feel daylight waning, mere minutes before the dusk. Only the girl’s bright shock of red, her dress, provides any kind of striking color. Then there’s her physical attitude. I think that when some young children read picture books where they can relate directly (and what could be more relatable than losing the person who is supposed to take care of you?) they can get anxious and take their cues from the characters’ physical attitudes. Flett’s girl is anxious, but physically she matches the wolf in demeanor. There’s a steady thrum of calm to these pictures, even as the situation starts to feel dire.

Children’s librarians are constantly asked to provide books full of “girl power” where the female characters have impetus and drive and are in charge of their own destinies. Such books often sport bright, eye-popping colors, and wild untamed girls that do battle with society’s mores and win. To these strong girl books I’d add The Girl and the Wolf. It’s not flashy or sparkly like the others. The girl in this book doesn’t work in a STEM field or break any barriers. Instead, she does something far more relatable. When caught in a stressful situation she takes stock, listens to sound advice, and thinks her way out of her predicament. That she does all this within the confines of what at first appears to be a Red Riding Hood-esque storyline just makes it all the more impressive. A clever twist on an old staple, and a much needed breath of fresh air for fairytale collections everywhere.

On shelves now.

Source: Copy borrowed from the library.

Filed under: Best Books, Best Books of 2019, Reviews, Reviews 2019

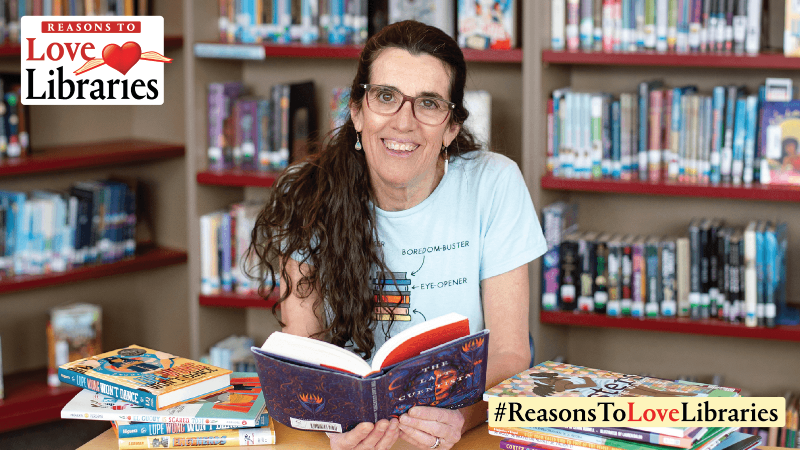

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Happy Poem in Your Pocket Day!

More Geronimo Stilton Graphic Novels Coming from Papercutz | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Environmental Mystery for Middle Grade Readers, a guest post by Rae Chalmers

ADVERTISEMENT

This book sounds fascinating from what you have written today. I thank you and will be sure to keep my eye out for it.