Guest Post: Happy Birthday Lore Segal! Ellen Handler Spitz Celebrates the Return of “Tell Me a Mitzi”

Dr. Ellen Handler Spitz is back! Today’s guest post celebrates a picture book classic, now back in print after decades of disappearance. Dr. Spitz puts the book in the context of not just its times but the canon of children’s literature itself. It’s too marvelous not to share widely. Consider it your required reading of the day:

Mitzi Is Back : Tell Me a Lore

2018 Ellen Handler Spitz

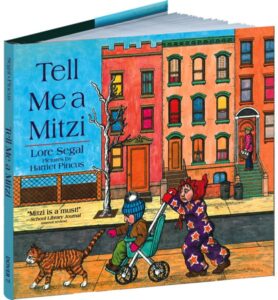

Lore Segal’s beloved picture book, Tell Me a Mitzi, is available once more! Published in 1970, by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, it fell out of print, and even its author does not know exactly when. But to the great joy of those who cherish it and to the future joy of those who will cherish it, it has been reissued by Dover (autumn 2017) with its original Harriet Pincus illustrations intact. Let’s pay homage, first off, to Jeff Golick, acquisitions editor at Dover, who instantly saw Mitzi’s genius and, unlike other editors approached by Lore’s devoted literary agent, various Mitzi aficionados, and myself, accomplished the feat of re-publishing this important children’s book. Bravo Jeff!

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Tell Me a Mitzi was designated a School Library Journal Best of the Best Book, a New York Times Outstanding Book of the Year, and a National Book Award Finalist.

Tell Me a Mitzi was designated a School Library Journal Best of the Best Book, a New York Times Outstanding Book of the Year, and a National Book Award Finalist.

No surprise. Acclaimed writer Lore Segal’s spare sentences and delectable inventions are more than illumined by Harriet Pincus’s detailed drawings in ink and full color. Trenchantly real, quaveringly surreal, Mitzi springs from a family’s daily life in New York City, vintage unspecified but apparently stretching from the 1950s to the late 1960s. Note: a milkman delivers in glass bottles. Harriet Pincus immerses us in cityscape: brownstones inside and out, storefronts, fire hydrants, street vendors, yellow taxi-cabs, one chalked hopscotch grid showing “POTSY,” a sidewalk jump-rope game, a watchful doorman in braid and blue. Her unidealized pictures feature squat, big-nosed, round-faced people, unbeautiful but cozy and comfortable; they create the external ambience for Lore’s prose, “a local habitation and a name,” as the Bard would have it. What rivets our attention, however, goes far beyond the external. It is Lore’s seamless transformation of the quotidian into the fanciful, which, uncannily, seems to come as effortlessly to her as breathing.

Each of Mitzi’s three chapters features a story with the same cast of family characters. There is a little girl called Martha, her baby brother Jacob, her mother, her father, and, in the middle—in a story about sneezing—her grandma. Martha, at the start of each chapter, asks for a story (“Tell me a Mitzi,” she begs), and one of her parents complies by recounting a tale that features Martha alias Mitzi.

Ordinary moments form the basis of each chapter. Everyone in the family comes down with a terrible cold; a young child wakes up before her parents have risen and seeks amusement; a father takes his children to a parade. Such routine events transmute into fantasy and adventure. Stunningly, however, adventure never passes beyond the limits of what children might actually fantasize. This is perhaps the greatest genius of the book. In the first story, Mitzi, after dressing her baby brother and herself in the early morning while her parents are asleep, hails a taxicab and, not realizing that a taxi-driver needs a street address, tries to visit their grandparents. Baby Jacob, who only repeats “Dadadada” to grownups, speaks perfect English to Mitzi. Before leaving, he peremptorily commands: “’Change my diaper.’” He even reminds his big sister that she must not go out in her pajamas. Later on in morning, back home again on the edge of her bed, Mitzi tells her mother she is too tired to take off her own pajamas and says, “’Mommy! Where do Grandma and Grandpa live?” “’Six West Seventy-seventh Street’” comes the reply, but “’Why do you ask?’” Mitzi’s expectable laconic rejoinder is “Because.”

Children love to share Mitzi’s secrets. They delight in the fact that baby Jacob, for instance, speaks clearly to her but not to grownups. This is both because Mitzi can imagine what he would be saying if he could speak properly and because she understands him better than they. On page after page, Lore reveals such insights and affords uncanny access to children’s inner worlds. An exquisite example occurs in the chapter called “Mitzi and the President.” Mitzi and Jacob are taken by their father to a parade. After all the excitement of the motorcade, the parade passes by, and little Jacob cries “’More.’” Tersely, his father responds, “’All gone. Lunchtime!’” But Jacob shouts louder and louder, calling for the parade to “’COME BACK.’” Then, lo! and behold: the parade does come back. Jacob’s plea is actually heard, and the President talks with Mitzi. The motorcade makes a U turn because, as the President says, there’s no reason why it should be going in one direction rather than the other. A perfectly logical child’s wish is allowed to come true. Only after that can Jacob, portrayed from the rear by Harriet Pincus in his short pants and suspenders, say the final words: “All gone,” as his father has done before. Jacob and the children listening to the story are now deeply satisfied. Lore Segal engages her audience at the precise level of their own imaginative powers.

Children love to share Mitzi’s secrets. They delight in the fact that baby Jacob, for instance, speaks clearly to her but not to grownups. This is both because Mitzi can imagine what he would be saying if he could speak properly and because she understands him better than they. On page after page, Lore reveals such insights and affords uncanny access to children’s inner worlds. An exquisite example occurs in the chapter called “Mitzi and the President.” Mitzi and Jacob are taken by their father to a parade. After all the excitement of the motorcade, the parade passes by, and little Jacob cries “’More.’” Tersely, his father responds, “’All gone. Lunchtime!’” But Jacob shouts louder and louder, calling for the parade to “’COME BACK.’” Then, lo! and behold: the parade does come back. Jacob’s plea is actually heard, and the President talks with Mitzi. The motorcade makes a U turn because, as the President says, there’s no reason why it should be going in one direction rather than the other. A perfectly logical child’s wish is allowed to come true. Only after that can Jacob, portrayed from the rear by Harriet Pincus in his short pants and suspenders, say the final words: “All gone,” as his father has done before. Jacob and the children listening to the story are now deeply satisfied. Lore Segal engages her audience at the precise level of their own imaginative powers.

Mitzi presents an exquisitely balanced collaboration between an artist who uses words to render the insides of children and an artist who uses pictures to show their outsides. This felicitous collaboration spells, I believe, Mitzi’s extraordinary appeal for nearly half a century. Revisiting the newly issued book for this essay, I wondered how Lore Segal achieves such apparently direct access when many other adults fall short. It seems fair to say that, despite paying close attention to children, looking and listening carefully to them, we adults—parents, teachers, librarians, therapists—find ourselves only rarely able to enter their inner worlds. Yet, for Lore Segal, this seems not to be the case.

Re-thinking Mitzi reminded me of a fascinating 1963 essay, “Meditations on a Hobby Horse” by the British art historian Ernst Gombrich. At what point, if ever, Gombrich asks, does child’s play becomes art? To explore this question, he takes the example of a hobby horse. A hobby horse, Gombrich points out, needs no head or mane or saddle. If a child wants to ride, all he or she needs is a simple stick. With this plain object, a child can pretend to gallop and elaborate marvelous fantasies. However, as Gombrich notes, the stick cannot on that account be considered art. If an artist, such as Picasso, he avers, were to send such a stick to an exhibition, people would find it satirical, ironic, or take it as a testament to the artist’s regard for humble things. What Picasso could never do is make the hobby horse mean to us what it meant to its first creator. “That way,” Gombrich firmly declares, “is barred by the angel with a flaming sword.” Saying this, he invokes the impossibility of any return to Eden.

Re-thinking Mitzi reminded me of a fascinating 1963 essay, “Meditations on a Hobby Horse” by the British art historian Ernst Gombrich. At what point, if ever, Gombrich asks, does child’s play becomes art? To explore this question, he takes the example of a hobby horse. A hobby horse, Gombrich points out, needs no head or mane or saddle. If a child wants to ride, all he or she needs is a simple stick. With this plain object, a child can pretend to gallop and elaborate marvelous fantasies. However, as Gombrich notes, the stick cannot on that account be considered art. If an artist, such as Picasso, he avers, were to send such a stick to an exhibition, people would find it satirical, ironic, or take it as a testament to the artist’s regard for humble things. What Picasso could never do is make the hobby horse mean to us what it meant to its first creator. “That way,” Gombrich firmly declares, “is barred by the angel with a flaming sword.” Saying this, he invokes the impossibility of any return to Eden.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Yet, this is precisely what Lore Segal accomplishes in Mitzi. Pondering and puzzling, I revisited her riveting novel/memoir Other People’s Houses, which was published serially by The New Yorker, starting in 1958, then as a book, and is being reissued this year in the United Kingdom with a splendid new Introduction. Other People’s Houses recounts Lore’s experience as a ten-year-old refugee, sent away from her native land, Austria, and from her parents, to that strange island, England, where people spoke a different language and where, over the next seven years, she lived with five foster families. In whom could she confide? Gifted with superior intelligence, an adaptive cast of mind, acute sensitivity, and a love of words, she must have kept secrets. Secrets from others who would not and could not understand her, secrets perhaps even from herself. To examine such hunches, I asked Lore Segal if she and I could meet. On February 20th, we enjoyed coffee and cake in her capacious Upper West Side apartment, the walls of which are hung with drawings by Maurice Sendak and William Steig. There is also an enticing home-made doll house that Lore constructed years ago for her daughter Beatrice.

Lore Segal sparkles. Fixing me with her sharp blue eyes, she cocks a curly head. She laughs gleefully at something we both find amusing. At nearly ninety, she radiates a spritely warmth; she speaks in matter of fact yet jubilant tones, tempered by a timbre of qualm and reserve. Her speech seems oracular. I find her irresistible yet slightly intimidating. Tiny of stature, she fills up all the surrounding space so that I am constrained from coming too close. Invited that winter morning, I bask hesitantly in her presence. Lore is, after all, one of those cursed-blessed children of 1938, simultaneously banished horrifically and rescued mercifully from Nazified Vienna. She was put on the first Kindertransport just months after Hitler had marched into Austria, her Jewish parents finding themselves threatened with depredation, deportation, and death. Willing their little girl to survive, they relinquished her. They let her go. But at what cost?

Lore Segal sparkles. Fixing me with her sharp blue eyes, she cocks a curly head. She laughs gleefully at something we both find amusing. At nearly ninety, she radiates a spritely warmth; she speaks in matter of fact yet jubilant tones, tempered by a timbre of qualm and reserve. Her speech seems oracular. I find her irresistible yet slightly intimidating. Tiny of stature, she fills up all the surrounding space so that I am constrained from coming too close. Invited that winter morning, I bask hesitantly in her presence. Lore is, after all, one of those cursed-blessed children of 1938, simultaneously banished horrifically and rescued mercifully from Nazified Vienna. She was put on the first Kindertransport just months after Hitler had marched into Austria, her Jewish parents finding themselves threatened with depredation, deportation, and death. Willing their little girl to survive, they relinquished her. They let her go. But at what cost?

Loving Mitzi, admiring, nay, marveling at it, I can only wonder what part was played in its genesis by the undeclared traumas of its author’s life and her steadfast, stalwart determination to endure. The secrets kept in childhood come flooding out in literary form, as simple, beautiful, wondrous stories for other children, not only to enjoy but also to use, so as to feel comprehended and therefore—as she herself never quite did—safe.

Thank you, Ellen, for that marvelous piece. Those of you who are still curious about the book might enjoy Marjorie Ingall’s Tablet Magazine article from 2015 called Lore Segal’s Warm and Weird “Tell Me a Mitzi”. And even further back, in 2010, it was featured on Vintage Kids’ Books My Kids Love.

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

Exclusive: Giant Magical Otters Invade New Hex Vet Graphic Novel | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

ADVERTISEMENT

Thanks for this wonderful piece. For some odd reason, I once ran into Lore Segal in E. Hardwick, VT and was completely awed. Wish I could remember the details.

Lore Segal attended an SCBWI party recently, and I was delighted to meet her and have a wonderful, long talk. I’ll never forget it.

And I’m having a long Twitter conversation with someone about how much she loves this book and your book BABY, Fran. Small world, eh?

Wow! Thanks, Betsy.

P. S. It’s going to be published in China!

Her 90th birthday is today! How appropros. I picture her and Judith Kerr hanging out together.

Appropos. I DO know how to spell.

WHOOOOOOOO!!!!!!

I love this article, the book, and the fact that it’s now available again. Will buy it just for me.