We Need Diverse Collectables: Why the Collectors of Children’s Books Need to Diversify

We need diverse books. But it’s not as simple as you think.

When I do presentations for up-and-coming authors and illustrators of children’s books I sometimes show them this slide:

Impossible to read here thanks to the teeny tiny type, this is my breakdown of the different factions that make up children’s literature. To spare your eyes I’ll just list them for you now:

Children’s Literature Fandom Simplified

- Bloggers

- International Focus

- Librarians

- Parents

- Authors/Illustrators

- Booksellers

- Academics

- Non-Profits

- Teachers

- Agents

- Publishers

- Collectors

I show this slide to new creators so that I can explain to them how different groups of people have different interests and attitudes towards books for kids. We all love them but sometimes we love them for very different reasons.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

In my peculiar situation as blogger/librarian/parent/author/reviewer, daughter of a bookseller, with a love of international titles, and the occasional academic paper under my belt (Routledge) I still have some gaps. I’m no teacher. I work for a library, but that’s different from a non-profit. I’m no agent (nor will I ever be) nor a publisher. Yet over the years I’ve constructed this crazed One World paradise view where I can someday see ALL these different aspects of books for kids working together, talking together and generally trying to make this world a better place.

What does this have to do with the We Need Diverse Books movement? Everything.

Let’s examine what we mean when we say we need diverse literature for kids. First off, we want new books being published today to not only present better representation on the page for children, but we want the publishers themselves to increase the number of voices from a variety of different races, perspectives, religions, and backgrounds within the publishing companies themselves. We want teachers to learn about these books and to share them with their students. We want bloggers to step out of their comfort zones and talk about more diverse titles. Librarians and booksellers to share them with the people who walk through their doors. International books are inherently diverse, but let’s see more representation from countries other than Europe. We want more voices writing and illustrating these books (#ownvoices), academics not just talk about them in papers but to also teach new librarians and teachers what’s available. We want parents to be informed, non-profits to spread the love of the best of these books, agents to represent more voices, you name it!!!

Did I forget anyone?

Ah yes.

Collectors.

You can’t pick and choose when it comes to diversity. Either we commit to this wholeheartedly or not at all. And so I ask you this – What is the most highly sought after children’s book written and/or illustrated by an African-American?

Why do I ask this question? Because when we talk about the people that collect children’s books, we’re talking about the people that assign a monetary worth to the books we work on or with so passionately. Most of us, I’d warrant, are unfamiliar with the world of the children’s book collectors. They’re a very specific group with, insofar as my research has indicated over the years, no overarching organization aside from that of general book collectors.

Years ago, I got a glimpse into their world. The Grolier Club in New York City was hosting the latest in its regular “One Hundred Books” series. This time it would be celebrating “One Hundred Books Famous in Children’s Literature”. Look at how vast that statement is. It does not limit any of these books by nation, creator, or time period. The sole stipulation would appear to be the fact that there need to be 100 of them. This can be misleading. As it turns out, exhibitions of this sort are often limited by the books they are able to attain at all. And so many collectors willingly lent their priceless books to the exhibit for a one-time-only showing. I saw such things . . . things like an edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland where Charles Lutwidge Dodgson had marked passages in purple ink that would be used for “The Nursery Alice” published later in 1889, which was abridged for younger children. Or an edition of The Little Engine That Could from 1930 that precedes the Watty Piper one we all know so well. Or an edition of Harry Potter (the most controversial inclusion in the exhibit, as far as I could ascertain) that was a very rare library edition (only 300 copies were ever made) given to public libraries and featuring a blurb on the cover from a “Wendy Cooling”. I have in my possession the accompanying book that went with this exhibit and it is amongst my most treasured possessions.

And yet . . . even a surface glance around the room revealed pretty early on the sheer lack of diversity in the collection. Yes, there was The Snowy Day and Uncle Remus, but they were both written by white guys, yes? Is there a reason why the collectors weren’t displaying any diverse titles? The book accompanying the exhibit poses this question: “what are the criteria for inclusion?” As it turns out, the criteria seemed to boil down to the fact that the books had to be “famous”. And THAT right there is the rub of it.

Collecting anything with an eye to its worth means that the book is, in some way, famous, yes? Either that or the collector is convinced that the book will become famous in the future. So is it true that no diverse children’s book is famous? What about a first edition of Heather Has Two Mommies? Original Caldecott winners and honors like Grandfather’s Journey or pretty much anything by John Steptoe wouldn’t count?

To this, I have no answer. After all, I’m no collector. I’m still floored by the fact that they don’t set much store by ARCs and galleys (the ultimate ephemeral collectable, as far as I can tell). But if we want diverse books then we want the collectors to realize that there is more to the literature than yet another copy of Curious George. Which brings me to Stallion Books. And back catalogs.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I think that there’s a danger that comes with celebrating books that are always new (said the person who only reviews books published in the current year on her blog). The new is shiny. The new is beautiful and pleasing to the eye and ear. New books are fun and who wouldn’t feel a thrill if you received a box of them like an award committee does? But in all the celebration of new diverse titles let us not forget the diverse authors and illustrators who were already in the trenches producing books for kids that served as windows and mirrors for decades upon decades. They didn’t have non-profits proclaiming their titles widely. They just knew how to make good books.

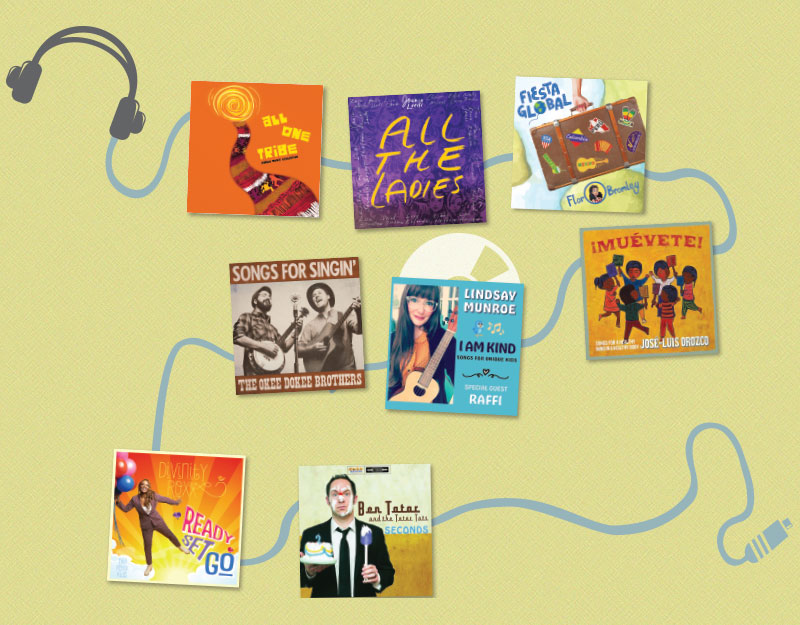

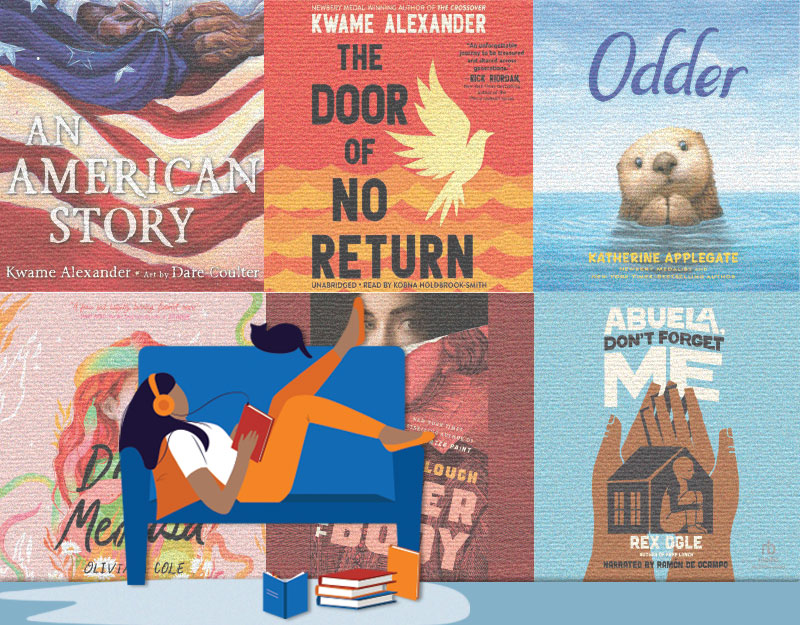

Yesterday in Chicago I attended the Printer’s Row Lit Fest. Book vendors from all over the city and authors of all kinds were present. And on Dearborn Street, not far from Gino’s East of Chicago, was a stand for Stallion Books. I was particularly intrigued when I saw the cover of this catalog:

Inside is the full back catalog of the three authors/illustrators mentioned: Ashley Bryan, Jan Spivey Gilchrist, and Eloise Greenfield. That description at the top proclaiming them to be “Three Legends” is no misnomer either. All three have been working in the field for decades upon decades and even travel together to promote their books. Find a children’s library worth its salt and you’ll find copious titles by them on the shelves. Looking through the catalog I saw a Collectors Set of 128 of their titles for sale for $3,490, which is a cheap price all things considered. I mean, you could diversify your library collection instantaneously with that purchase.

Paging through the catalog, I got to thinking about why it is that children’s book collectors don’t know enough to realize that an original edition of any one of these authors’ books would be a sound investment. I suppose collectors only know as much as they themselves are taught. Many of them probably collect the books they read as children. With that thought in mind, let us hope that the kids of the 21st century are seeing books like those of Ashley Bryan, Jan Spivey Gilchrist, and Eloise Greenfield so that when they grow up and collect books for professional reasons, they’ll see the worth of these titles from both a monetary and a personal standpoint.

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

The Moral Dilemma of THE MONSTER AT THE END OF THIS BOOK

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

ADVERTISEMENT

Insightful article.

But could we possibly add “children” to the fandom breakdown?

I mean they are who most of us write for…

Kids, eh? It’s a revolutionary concept but I’ll accept it.

The do sort of get lost in the shuffle, don’t they? To be honest, the slide is usually shown as a way of indicating all the folks who work for children’s books and what it takes to alert each one when you have a new book out. Does sort of leave out the primary recipients, but I was taking them as a given. That’s the danger in this business. Remember the product, forget the purpose.

It’s easy to think of the kids as a given, but they really aren’t. There is a certain frustration in having carefully curated as diverse as collection as possible, only to have your highly diverse student population head straight for the Wimpy Kids every time. And I do know that a big part of my job as a school librarian is to gently open up their minds to the other 6,990 books in my collection, give or take, but if it’s Wimpy Kid they really want, it’s Wimpy Kid they will get.

Somewhat similar discussion yesterday in our story time – why is the default number of children in a fictional family two, and it’s almost always a boy and a girl? I could only think of three families I know who have exactly one boy and one girl, and I’m not sure that any of them are ‘done’. I have many many MANY families with four or more children, but you rarely see that in picture books.

Similar to the ‘remember the kids’ thread, not the original post – not articulating well today:)

One of the reasons I like Shannon Hale’s new book REAL FRIENDS so much. Big big big Mormon families in that one. No one boy/one girl fams to be seen.

Ooh, awesome! While I’m in southern NM, there is a strong Mormon community here, so it will be nice to have a new book to hand off to them. In the middle of fiscal year switcharounds, so my order card is sitting here patiently waiting…

We have four families amongst the active population of our Sunday School class with exactly two children in their family — one boy and one girl.

Our pastor and his wife have two children, one boy and one girl.

Two other families have three boys

One has two boys and may not be done

The one that just moved has two boys and 1 girl

Another couple is pregnant with their first child, unknown what it will be yet.

Dear Betsy,

I remember the Grolier exhibition too. It was fascinating but indeed deeply white. Leonard Marcus’ The ABC of It and my own 2008 exhibit, Artifacts of Childhood, tried to include international materials and ethnicities, but I don’t think we were successful enough. I’d like to see a major exhibit of historical African-American children’s literature but who would host it?

I think what collectors will not admit is that the African-American related children’s books that are collected are editions of Little Black Sambo and the like. Those are the “famous” books. I’ve heard of some collections that focus on images of African-American children in children’s books, past and present, and again, that includes deeply problematic stuff.

On Pinterest, I hunt for historical illustrations of African-American children from vintage children’s books and so many of them are problematic…

I’ve picked up some stuff from the 1960s-1970s to save them in my own collection and it may be that there are collectors out there who work quietly to develop collections that will come to special collection libraries in due time.

I wish there was a way to encourage the collection of African-American children’s books in a formal manner, not just haphazardly.

Frustratedly yours,

Jenny

Hi Jenny,

I’m glad you brought this up because it’s something I’ve been brooding over as well. Things that are collectable are rare and often these days they are rare because they are offensive. Sambo fits the bill, as would the books you mentioned, and most recently first editions of A Birthday Cake for George Washington. And the obvious and best place for a major exhibit of historical African-American children’s literature – The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at NYPL, of course! I know for a fact that there’s a collection in the Countee Cullen Branch next door (if they haven’t gotten rid of it) of children’s literature.

I’m thinking about what role, if any, art museums might play in this. I’m specifically wondering if fine art museums that exhibit works of picturebook illustrators might act as a sort of stamp of approval to signify to collectors that this particular illustrator’s work is worthy of investment.

If this is true, the question then becomes who are the illustrators whose picturebook artwork are exhibited in museums.

Well I know that the Met has a lovely children’s library and that they do a lot with the art there. MOMA has been known to do events, if not exhibits. Brandywine too, I think. But it does appear to be the exception rather than the rule.