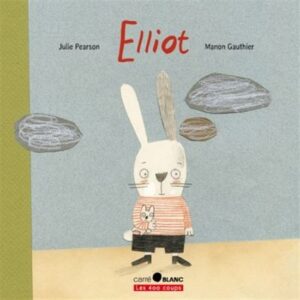

Review of the Day: Elliot by Julie Pearson

Elliot

Elliot

By Julie Pearson

Translated by Erin Woods

Illustrated by Manon Gauthier

Pajama Press

$16.95

ISBN: 978-1-927485-85-9

Ages 4-7

On shelves April 4th

The librarian and the bookseller face shelving challenges the like of which you wouldn’t believe. You think all picture books should simply be shelved in the picture book section by the author’s last name and that’s the end of it? Think again. If picture books served a single, solitary purpose that might well be the case. But picture books carry heavy burdens, far above and beyond their usual literacy needs. People use picture books for all sorts of reasons. There are picture books for high school graduates, for people to read aloud during wedding ceremonies, for funerals, and as wry adult jokes. On the children’s side, picture books can help parents and children navigate difficult subjects and topics. From potty training to racism, complicated historical moments and new ways of seeing the world, the picture book has proved to be an infinitely flexible object. The one purpose that is too little discussed but is its most complicated and complex use is when it needs to explain the inexplicable. Cancer. Absentee parents. Down syndrome. Explaining just one of these issues at a time is hard. Explaining two at one time? I’d say it was almost impossible. Julie Pearson’s book Elliot takes on that burden, attempting to explain both the foster system and children with emotional developmental difficulties at the same time. It works in some ways, and it doesn’t work in others, but when it comes to the attempt itself it is, quite possibly, heroic.

Elliot has a loving mother and father, that much we know. However, for whatever reason, Elliot’s parents have difficulty with their young son. When he cries, or yells, or misbehaves they have no idea how to handle these situations. So the social worker Thomas is called in and right away he sets up Elliot in a foster home. There, people understand Elliot’s needs. He goes home with his parents, after they learn how to take care of him, but fairly soon the trouble starts up again. This time Thomas takes Elliot to a new foster care home, and again he’s well tended. So much so that even though he loves his parents, he worries about going home with them. However, in time Thomas assures Elliot that his parents will never take care of him again. And then Thomas finds Elliot a ‘forever” home full of people who love AND understand how to take care of him. One he never has to leave.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Let me say right here and now that this is the first picture book about the foster care system, in any form, that I have encountered. Middle grade fiction will occasionally touch on the issue, though rarely in any depth. Yet in spite of the fact that thousands and thousands of children go through the foster care system, books for them are nonexistent. Even “Elliot” is specific to only one kind of foster care situation (children with developmental issues). For children with parents who are out of the picture for other reasons, they may take some comfort in this book, but it’s pretty specific to its own situation. Pearson writes from a place of experience, and she’s writing for a very young audience, hence the comforting format of repetition (whether we’re seeing Elliot’s same problems over and over again, or the situation of entering one foster care home after another). Pearson tries to go for the Rule of Three, having Elliot stay with three different foster care families (the third being the family he ends up with). From a literary standpoint I understand why this was done, and I can see how it reflects an authentic experience, but it does seem strange to young readers. Because the families are never named, their only distinguishing characteristics appear to be the number of children in the families and the family pets. Otherwise they blur.

Let me say right here and now that this is the first picture book about the foster care system, in any form, that I have encountered. Middle grade fiction will occasionally touch on the issue, though rarely in any depth. Yet in spite of the fact that thousands and thousands of children go through the foster care system, books for them are nonexistent. Even “Elliot” is specific to only one kind of foster care situation (children with developmental issues). For children with parents who are out of the picture for other reasons, they may take some comfort in this book, but it’s pretty specific to its own situation. Pearson writes from a place of experience, and she’s writing for a very young audience, hence the comforting format of repetition (whether we’re seeing Elliot’s same problems over and over again, or the situation of entering one foster care home after another). Pearson tries to go for the Rule of Three, having Elliot stay with three different foster care families (the third being the family he ends up with). From a literary standpoint I understand why this was done, and I can see how it reflects an authentic experience, but it does seem strange to young readers. Because the families are never named, their only distinguishing characteristics appear to be the number of children in the families and the family pets. Otherwise they blur.

Pearson is attempting to make this accessible for young readers, so that means downplaying some of the story’s harsher aspects. We know that Elliot’s parents are incapable of learning how to take care of him. We are also assured that they love him, but we never know why they can’t shoulder their responsibilities. This makes the book appropriate for young readers, but to withdraw all blame on the parental side will add a layer of fear for those kids who encounter this book without some systematic prepping beforehand. It would be pretty easy for them to say, “Wait. I sometimes cry. I sometimes misbehave. Are my parents going to leave me with a strange family?”

Artist Manon Gauthier is the illustrator behind this book and here she employs a very young, accessible style. Bunnies are, for whatever reason, the perfect animal stand-in for human problems and relationships, and so this serious subject matter is made younger on sight. With this in mind, the illustrator’s style brings with it at least one problematic issue. I suspect that many people that come to this book will approach it in much the same way that I did. My method of reading picture books is to grab a big bunch of them and carry them to my lunch table. Then I go through them and try to figure out which ones are delightful, which ones are terrible, and which ones are merely meh (that would be the bulk). I picked up Elliot and had the reaction to it that I’m sure a lot of people will. “Aw. What a cute little bunny book” thought I. It was around the time Elliot was taken from his family for the second time that I began to catch on to what I was reading. A fellow children’s librarian read the book and speculated that it was the choice of artist that was the problem. With its adorable bunny on the cover there is little indication of the very serious content inside. I’ve pondered this at length and in the end I’ve decided that it’s not the style of the art that’s problematic here but the choice of which image to show on the book jacket. Considering the subject matter, the publisher might have done better to go the The Day Leo Said, ‘I Hate You’ route. Which is to say, show a cover where there is a problem. On the back of the book is a picture of Elliot looking interested but wary on the lap of a motherly rabbit. Even that might have been sufficiently interesting to make readers take a close read of the plot description on the bookflap. It certainly couldn’t have hurt.

Artist Manon Gauthier is the illustrator behind this book and here she employs a very young, accessible style. Bunnies are, for whatever reason, the perfect animal stand-in for human problems and relationships, and so this serious subject matter is made younger on sight. With this in mind, the illustrator’s style brings with it at least one problematic issue. I suspect that many people that come to this book will approach it in much the same way that I did. My method of reading picture books is to grab a big bunch of them and carry them to my lunch table. Then I go through them and try to figure out which ones are delightful, which ones are terrible, and which ones are merely meh (that would be the bulk). I picked up Elliot and had the reaction to it that I’m sure a lot of people will. “Aw. What a cute little bunny book” thought I. It was around the time Elliot was taken from his family for the second time that I began to catch on to what I was reading. A fellow children’s librarian read the book and speculated that it was the choice of artist that was the problem. With its adorable bunny on the cover there is little indication of the very serious content inside. I’ve pondered this at length and in the end I’ve decided that it’s not the style of the art that’s problematic here but the choice of which image to show on the book jacket. Considering the subject matter, the publisher might have done better to go the The Day Leo Said, ‘I Hate You’ route. Which is to say, show a cover where there is a problem. On the back of the book is a picture of Elliot looking interested but wary on the lap of a motherly rabbit. Even that might have been sufficiently interesting to make readers take a close read of the plot description on the bookflap. It certainly couldn’t have hurt.

Could this book irreparably harm a child if they encountered it unawares? Short Answer: No. Long Answer: Not even slightly. But could they be disturbed by it? Sure could. I don’t think it would take much stretch of the imagination to figure that the child that encounters this book unawares without any context could be potentially frightened by what the book is implying. I’ll confess something to you, though. As I put this book out for review, my 4-year-old daughter spotted it. And, since it’s a picture book, she asked if I could read it to her. I had a moment then of hesitation. How do I give this book enough context before a read? But at last I decided to explain beforehand as much as I could about children with developmental disabilities and the foster care system. In some ways this talk boiled down to me explaining to her that some parents are unfit parents, a concept that until this time had been mercifully unfamiliar to her. After we read the book, her only real question was why Elliot had to go through so many foster care families, so we got to talk about that for a while It was a pretty valuable conversation and not one I would have had with her without the prompting of the book itself. So outside of children that have an immediate need of this title, there is a value to the contents.

What’s that old Ranganathan rule? Ah, yes. “Every book its reader.” Trouble is, sometimes the readers exist but the books don’t. Books like Elliot are exceedingly rare sometimes. I’d be the first to admit that Pearson and Gauthier’s book may bite off a bit more than it can chew, but it’s hardly a book built on the shaky foundation of mere good intentions. Elliot confronts issues few other titles would dare, and if it looks like one thing and ends up being another, that’s okay. There will certainly be parents that find themselves unexpectedly reading this to their kids at night only to discover partway through that this doesn’t follow the usual format or rules. It’s funny, strange, and sad but ultimately hopeful at its core. Social workers, teachers, and parents will find it one way or another, you may rest assured. For many libraries it will end up in the “Parenting” section. Not for everybody (what book is?) but a godsend to a certain few.

On shelves April 4th.

Source: Galley sent from publicist for review.

Filed under: Reviews, Reviews 2016

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

One Star Review, Guess Who? (#202)

Exclusive: Giant Magical Otters Invade New Hex Vet Graphic Novel | News

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Take Five: LGBTQIA+ Middle Grade Novels

ADVERTISEMENT

Good job of discussing all the challenges in Elliot, particularly for booksellers-in-a-hurry who will be inclined to put this on a spring/Easter table unless they’ve read your review.

Also, can I put in a pitch for a Jill Wolfson’s wonderful novel, What I Call Life? Its protagonist lives in a foster care run by the Knitting Lady, a woman whose personal history and storytelling gifts give her charges a sense that foster children have a culture of their own: a history, from Moses on, that can be a source of strength.

Appreciations for this review, BB.