SBBT: Kekla Magoon Interview

Fuse #8: Okay. So for years I’ve been trying to find works of children’s literature that discuss The Black Panthers in some way, shape, or form. And basically, I’ve come up blank. Then your book comes along and finally provides a little of what I’m looking for. What gave you the idea in the first place?

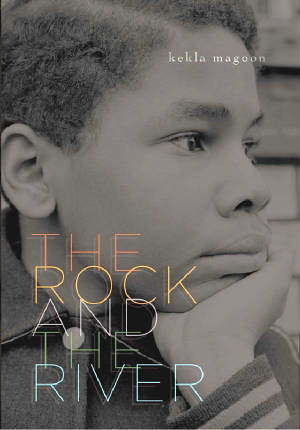

Kekla Magoon: The story that became The Rock and the River first floated into my mind as a series of scenes between two boys walking on the street. One older, one younger. Brothers. The younger felt confused, the older defiant. Both wanting something. I didn’t know what. Something important, something slightly out of reach….

To be honest, I knew what the story was from these first wisps of a beginning. I was marginally excited about it, massively intrigued by it….and utterly afraid of it. But I went ahead and worked on it because I didn’t think it would matter. I was sure it had been done before – a novel about the Black Panthers for teens. They’re much too interesting not to have been written about before, and they were mostly young, so…come on. But I couldn’t find anything.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

When I wrote the first scene (not the novel’s opening), I’d recently read something about The Black Panthers online that surprised me – the fact that they ran a free breakfast program for school children. As I learned more about them, I graduated from surprise to shock to outrage that I hadn’t known about the depth of the Panthers’ community engagement before. I’d only ever heard about their militancy. That realization more than anything fueled my desire to finish the book. I wanted to put something out in the world that offered a different image of the Panthers than what I’d grown up believing. But…that’s really an intellectual argument for why I wanted the book to be published, and I’m honestly not sure it would have been enough to get it written.

The idea for this book could have come and gone from my head if not for one other little thing that keeps bothering me: What would I have done? I’m teased by that question, even now. What choices would I have made, if I’d lived in the time and place that I positioned my characters? In the end, I didn’t write The Rock and the River to fill a void in the market, though I’m deeply glad to have done that. I wrote it because it’s the closest I could come to feeling what life was like in 1968, a time period that has always intrigued me.

Fuse #8: Have you had any discussions with any of the real Panthers about your title? What about Civil Rights activists? I would think the kids of activists would definitely understand the boredom of standing at rallies all the time.

Fuse #8: Have you had any discussions with any of the real Panthers about your title? What about Civil Rights activists? I would think the kids of activists would definitely understand the boredom of standing at rallies all the time.

KM: I’ve talked with a lot of people who were around in the 1960s, including some folks who were peripherally involved with the Panthers and many who were civil rights activists in some way or another. I’ve also talked to people who were children at the time, and it’s striking how vivid their memories of 1968 in particular are, and how eager they are to talk about those stories, even the strange and painful ones.

For me, this has been one of the best results of having The Rock and the River published. The novel has been out for almost six months at this point. In that time, I’ve received dozens of notes and stories from people (some friends, some strangers) wanting to tell me where they were and what they were doing that year. The volume and variety of stories I’m getting is incredible. I love these conversations, and it thrills me deeply that the book resonates with people across lines of race and generation.

In the research phase of writing, I didn’t do a lot of interviews. Maybe I was too timid about approaching folks, or maybe I asked the wrong questions, but I couldn’t get through to people. So, I read biographies and histories and watched films and documentaries, but beyond that I drew upon my creativity and imagination. Now, the “interviewees” are coming out of the woodwork.

My theory about why this is happening? The year 1968 was a watershed moment in U.S. history, but one that goes un-talked about. People didn’t know what to make of me when I asked about it. Once they’ve read the book, they see that I’m not after the facts and figures of what was going on, but how people felt about the world at the time. And they’re ready to spill all because those feelings have stayed with them, and they’ve never had a chance to talk about them before.

Fuse #8: The book takes place primarily in Chicago. Are you a former Chicagoan yourself? Why the choice of that particular burg?

KM: Well, I grew up in northern Indiana and I attended Northwestern University (just north of the city) so I had spent a fair amount of time in Chicago. Familiarity definitely influenced my choice of setting. But when I started writing the story, I didn’t know where it was going to take place. The only inklings I had were “urban” and “North.” Research came into play a bit here. For the story backdrop to be as I wanted it, I needed a northern city, where Dr. King had visited within a year of his death, where riots occurred in the wake of his assassination, and where the Panthers eventually were active. All signs pointed to Chicago.

Fuse #8: Some authors I know will dedicate a significant amount of time and research to a topic and then wash their hands of the project afterwards. Others will follow up their fictional books with non-fiction offerings on the same topic. Considering the amount of time and effort that went into researching the Panthers, have you ever considered writing a non-fiction title about them for kids?

Fuse #8: Some authors I know will dedicate a significant amount of time and research to a topic and then wash their hands of the project afterwards. Others will follow up their fictional books with non-fiction offerings on the same topic. Considering the amount of time and effort that went into researching the Panthers, have you ever considered writing a non-fiction title about them for kids?

KM: Yes, I have an interest in doing so. A strong interest. Not only because of the volume of research I’ve already done, but also because there isn’t anything out there like it. Frankly, I’d have to do much more research (and some re-research!) to write an effective non-fiction piece, but that process would be both worthwhile and exciting for me. What I envision is a book that isn’t solely or specifically about The Black Panthers, but one that offers a slightly different perspective on the civil rights movement as a whole. A story of how things looked in-the-moment rather than how they look in hindsight, when we know what the endgame is. (Uh-oh. See, now you’ve inspired me to jump on my soapbox…)

I’ve realized in writing this book that the way we tell history to kids is very hero-focused. It’s especially true of Black History. How does the story go? There was slavery, then Abraham Lincoln. Segregation, then Rosa Parks. Then Dr. King came along, and now we’re all living happily ever after. Ummm….simplified much? I’m being slightly facetious here, but not totally. What’s left out of that narrative – for civil rights in particular – is how many ordinary people were involved. This was a movement of the people, and of young people in particular: freedom rides, lunch counter sit-ins, SNCC, and so on. And it wasn’t easy. Now, looking back, we talk about “marching.” Protest. Non-violence. No. The social change that happened was the result of courage on the part of everyday people, the result of terror being set aside in favor of a thirst for justice, the result of literal blood in the streets. Millions of people overcame fear and oppression and stood up. Isn’t that a legacy to be proud of? As much or more so than the words of one exceptionally eloquent leader?

As a twenty-something person, I feel rather steeped in a particular knowledge of the civil rights era that’s been handed down to me from my parents’ generation. Before writing this book, I mistakenly assumed that all school kids feel the same. Not so. I’m doing school visits now, and the middle schoolers I speak to don’t know those stories, don’t know that history. They stare blankly when I mention dogs and firehoses, they’ve never heard of the freedom rides, my book’s reference to “ketchup on their heads” doesn’t evoke thoughts of lunch counter sit-ins by college students, the phrase “four little girls” means nothing to them. All they know is Rosa Parks and Dr. King; they can define segregation and recite passages from the “I Have a Dream” speech. I don’t think it’s fair that they’re not getting the whole story.

As a twenty-something person, I feel rather steeped in a particular knowledge of the civil rights era that’s been handed down to me from my parents’ generation. Before writing this book, I mistakenly assumed that all school kids feel the same. Not so. I’m doing school visits now, and the middle schoolers I speak to don’t know those stories, don’t know that history. They stare blankly when I mention dogs and firehoses, they’ve never heard of the freedom rides, my book’s reference to “ketchup on their heads” doesn’t evoke thoughts of lunch counter sit-ins by college students, the phrase “four little girls” means nothing to them. All they know is Rosa Parks and Dr. King; they can define segregation and recite passages from the “I Have a Dream” speech. I don’t think it’s fair that they’re not getting the whole story.

Okay…soapbox time is over. Obviously, no middle school history class can cover all the bases of any given era, but this is recent history and still-relevant history. In my opinion, it’s much too soon to cram “civil rights” into a tiny box in a museum, or a tiny paragraph in a textbook.

Fuse #8: I’ve noticed that you’ve been doing some work with some kind of Hunger Mountain thingy thing. I honestly have no idea what this is. Care to fill me in?

KM: Sure! It’s pretty exciting, actually. Hunger Mountain is the arts journal of Vermont College of Fine Arts. Previously, the journal has been a print publication featuring adult market fiction, non-fiction and poetry. This summer, HM is going online and the new website will include a section for YA & Children’s Literature! Most exciting of all, I’ve been named Co-Editor of this new YA and Children’s component of the journal, along with fellow author Bethany Hegedus.

What does this mean? Well. This spring, Bethany and I have worked with the managing editor up at Hunger Mountain to develop content for a literary magazine that will showcase YA & children’s literature online! Half of our section will feature articles, essays, interviews and opinion pieces on the writing life, craft, the publishing industry, controversial issues, kidlit hot topics, and much more. The other half will feature fiction, non-fiction and poetry written for youth of all ages. The target audience of our journal is adults, but those who care about quality children’s literature.

What does this mean? Well. This spring, Bethany and I have worked with the managing editor up at Hunger Mountain to develop content for a literary magazine that will showcase YA & children’s literature online! Half of our section will feature articles, essays, interviews and opinion pieces on the writing life, craft, the publishing industry, controversial issues, kidlit hot topics, and much more. The other half will feature fiction, non-fiction and poetry written for youth of all ages. The target audience of our journal is adults, but those who care about quality children’s literature.

What do we publish? We’re open to an unlimited variety of material and subject matter for new fiction, poetry and creative non-fiction, as long as it represents your best work. In addition to highly-polished new pieces, we’d love to see deleted scenes from published books, the short story that launched a novel, or samples from a picture book artist’s sketchbook. Our first submission deadline has passed, but we’ll soon have an online submission process and guidelines posted on the site, www.hungermtn.org. In the meantime, check out our ongoing writing contest.

I’m thrilled to be involved with Hunger Mountain! It’ll be a fresh and unique resource for the children’s writing community. Here are just a few of the authors who contributed work for the launch: Katherine Paterson, Andrew Auseon, Sundee T. Frazier, Carrie Jones, Greg Neri, K.A. Nuzum, Susan Patron, Rita Williams-Garcia, Tim Wynne-Jones and Sara Zarr.

We’re scheduled to launch at the end of June!

Fuse #8: And finally, of course, what are you working on literary-wise at this moment in time? What’s on the menu?

KM: Oh, many, many things! I always have multiple projects in-progress at the same time. First and foremost, I’m working on a contemporary middle grade novel that will be published by Aladdin/Simon & Schuster. I can’t describe it for you, since I’m still writing and the story hasn’t told me everything about what it’s going to be yet! I don’t have a title, either, but I can tell you that the main character is a biracial girl. And I think it may be set in Nevada, which is totally weird, since I know nothing about Nevada except that it has Las Vegas, where I’ve never been. Hmmm. And…when I’m not puttering along on that piece, I’m also re-revising a YA novel draft, and I’m brainstorming scenes for a new one! I find that I can’t write one novel from beginning to end, then move on to the next, like some authors do. My inspiration toward each piece ebbs and flows, and I follow the pull of my creativity. It all works out in the end!

Thanks, Betsy, for inviting me to stop by Fuse #8! This was fun!

Filed under: Uncategorized

About Betsy Bird

Betsy Bird is currently the Collection Development Manager of the Evanston Public Library system and a former Materials Specialist for New York Public Library. She has served on Newbery, written for Horn Book, and has done other lovely little things that she'd love to tell you about but that she's sure you'd find more interesting to hear of in person. Her opinions are her own and do not reflect those of EPL, SLJ, or any of the other acronyms you might be able to name. Follow her on Twitter: @fuseeight.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

2024 Books from Pura Belpré Winners

Winnie-The-Pooh | Review

Parsing Religion in Public Schools

Finding My Own Team Canteen, a cover reveal and guest post by Amalie Jahn

ADVERTISEMENT

I don’t know how I missed this one but I’m getting a copy – now. And I hope she writes that NF title on the Panthers because everything she is saying about teaching black history is dead on. My students (college level) knew very little beyond King, Parks and Brown v Board of Education. I knew it was bad when I mentioned the Scottsboro boys the first time and you could have heard a pin drop.

Excellent interview Betsy!

Great interview. The Rock and the River is a wonderful book, and I love Kekla Magoon’s soapbox.

Thank you very much for this interview, Betsy and Kekla! Now I want to read The Rock and the River!

Kekla,

When I read this paragraph it brought tears to my eyes. Seriously.

“The social change that happened was the result of courage on the part of everyday people, the result of terror being set aside in favor of a thirst for justice, the result of literal blood in the streets. Millions of people overcame fear and oppression and stood up. Isn’t that a legacy to be proud of? As much or more so than the words of one exceptionally eloquent leader?”

You are amazing as a writer and a person.

Betsy, Thank you so much for this interview. It was really well done.

After your February review, I promptly read a library copy and loved it. After reading this interview, I promptly BOUGHT the book, so I can share it with the youngsters I know. BTW, do you know if there is an equivalent book about the United Farm Workers that is ordinary-people and “movement” focused?

Kekla Excellent work! I am very proud of you.